-

History & Society

- Education in Pre-war Hong Kong

- History of Taikoo Sugar Refinery

- Hong Kong Products Exhibition

- Local Festivals Around the Year

- Post-war Industries

- Pre-war Industry

- The Hong Kong Jockey Club Archives

- Tin Hau Festival

- Memories We Share: Hong Kong in the 1960s and 1970s

- History in Miniature: The 150th Anniversary of Stamp Issuance in Hong Kong

- A Partnership with the People: KAAA and Post-war Agricultural Hong Kong

- The Oral Legacies (I) - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong

- Hong Kong Currency

- Hong Kong, Benevolent City: Tung Wah and the Growth of Chinese Communities

- The Oral Legacies Series II: the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong

- Braving the Storm: Hong Kong under Japanese Occupation

- A Century of Fashion: Hong Kong Cheongsam Story

Geography & EnvironmentArt & Culture- Calendar Posters of Kwan Wai-nung

- Festival of Hong Kong

- Ho Sau: Poetic Photography of Daily Life

- Hong Kong Cemetery

- Sketches by Kong Kai-ming

- The Culture of Bamboo Scaffolding

- The Legend of Silk and Wood: A Hong Kong Qin Story

- Journeys of Leung Ping Kwan

- From Soya Bean Milk To Pu'er Tea

- Applauding Hong Kong Pop Legend: Roman Tam

- 他 FASHION 傳奇 EDDIE LAU 她 IMAGE 百變 劉培基

- A Eulogy of Hong Kong Landscape in Painting: The Art of Huang Bore

- Imprint of the Heart: Artistic Journey of Huang Xinbo

- Porcelain and Painting

- A Voice for the Ages, a Master of his Art – A Tribute to Lam Kar Sing

- Memories of Renowned Lyricist: Richard Lam Chun Keung's Manuscripts

- Seal Carving in Lingnan

- Literary Giant - Jin Yong and Louis Cha

-

History & SocietyGeography & EnvironmentArt & Culture

-

View Oral History RecordsFeatured StoriesAbout Hong Kong Voices

-

Hong Kong MemoryPost-war IndustriesRecently Visited

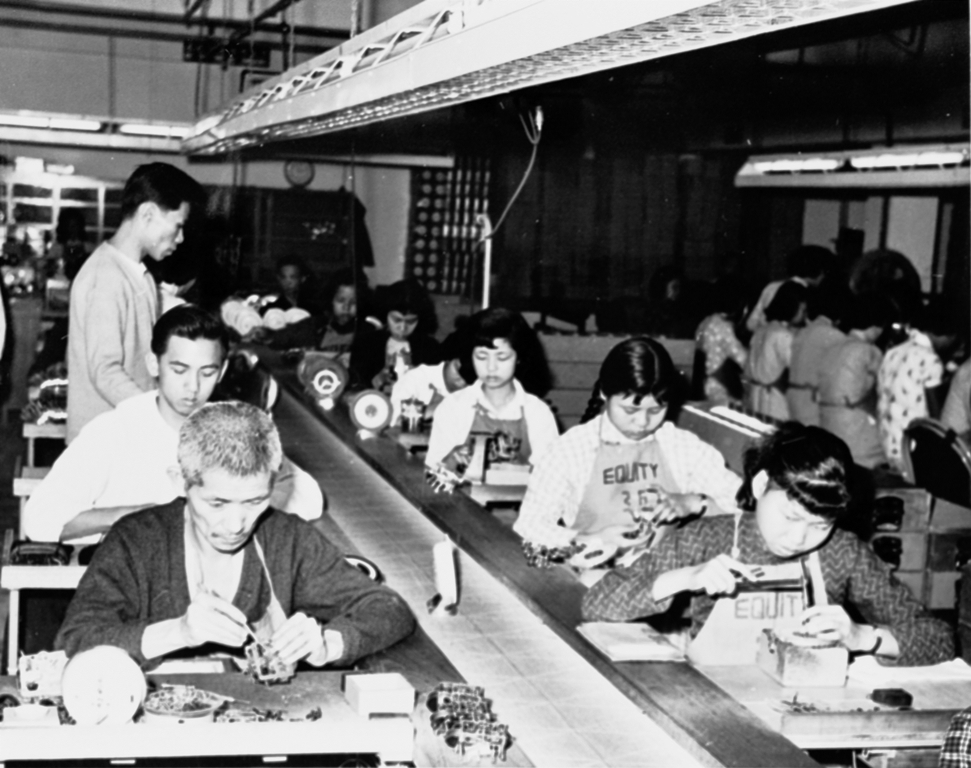

Industrialization in Post-war Hong Kong

-

The Rise and Decline of Hong Kong Industry

Industrial development in Hong Kong has a long history. Making boats and shipping related industries were the first to develop. More heavy industries developed by European companies. In the early 20th century, Chinese merchants established factories in Hong Kong, stimulating such industries as textile and the manufacturing of rubber shoes and torches. By the time of Japanese occupation, local industries had already made much progress. Industrial production was almost halted during the occupation but revived quickly after the War. Shanghai industrialists brought in capital and technical knowhow with them; large numbers of refugees provided an immense pool of cheap labour; capitals moved from trading to manufacturing under the impact of Korean War; the opening of markets in the United States and Europe saw further progress in Hong Kong’s industrialization.

In the 1960s, Hong Kong was the export centre of manufactured products in East Asia. The following decade saw the spread of Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEM) as Hong Kong became the production base of many overseas brand products. In the 1980s, labour-intensive production processes were relocated to the north. Small and medium sized enterprises moved the whole factory to China; some of the larger and more energetic companies engaged in retail trade and brand development. This trend has continued into the 2000s.

-

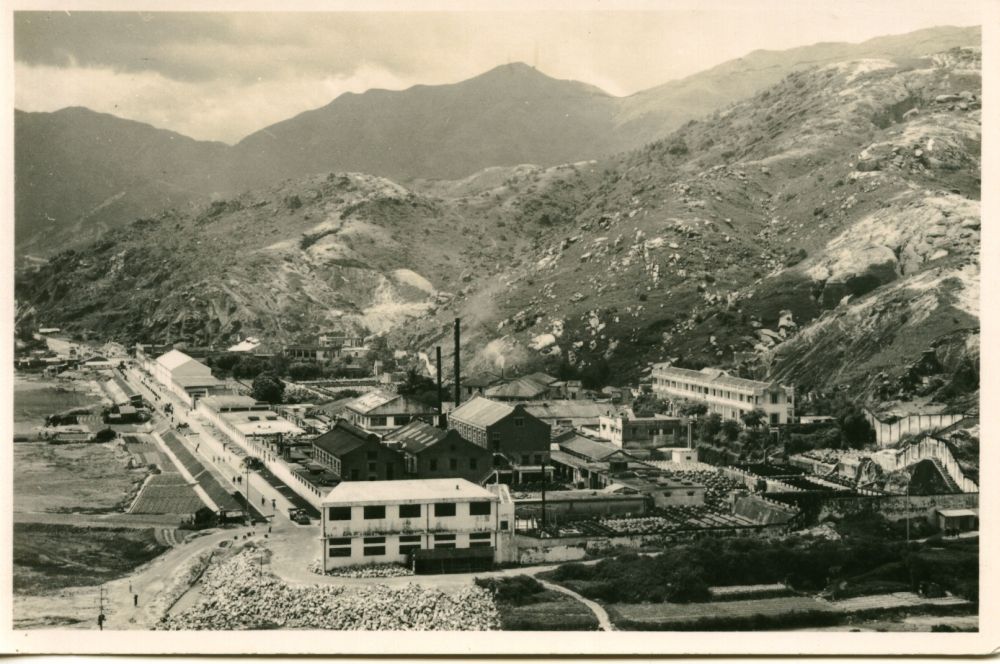

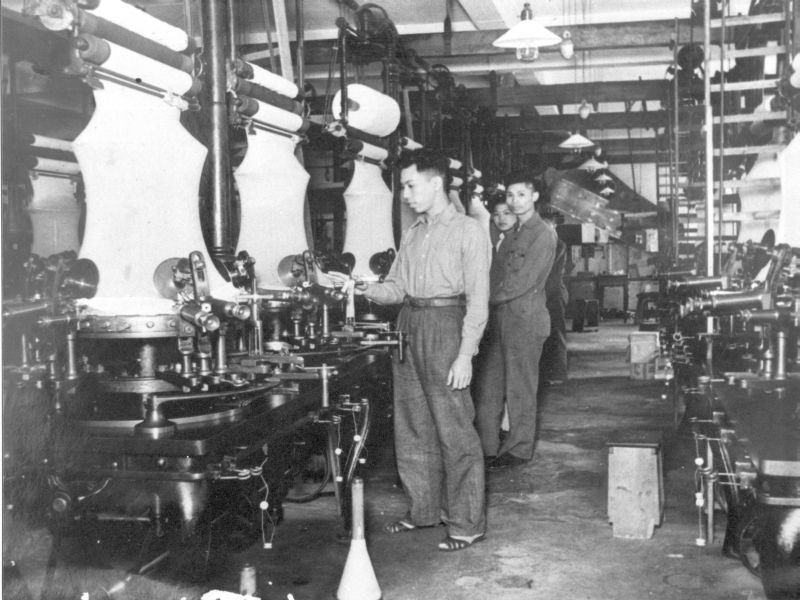

Industry in Prewar Hong Kong

Hong Kong has a long history of industry. As early as 1870, the government had recorded local manufacturing and production activities. These were mainly related to shipping such as the making of junks, rope and machine parts. In addition, food processing was also important including refined sugar, preserved ginger, preserved fruits and lard for sale overseas and on the mainland. In the early 1900s, Chinese manufacturers started to use machinery for production; the earliest machine-produced goods included cotton vests, socks, rattan furniture and paper for printing. More factories were founded when Chinese capitalists arrived in the 1920s and 30s from Southeast Asia, Shanghai and Guangzhou, introducing modern management into their industrial enterprises.

Imperial Preference began in 1932. Hong Kong enjoyed tax privileged tax for products imported into the British Empire and its territories. This had boosted cotton fabrics and the manufacture of rubber shoes, torches and batteries. On the eve of the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong, there were 1,200 registered factories and the industrial workforce was over 90,000. However, during the Japanese occupation that followed, many of the factories were either sequestered by the Japanese army or destroyed. Many factory owners fled and industrial production came to a virtual standstill.

-

Restoring Industries After the War

The Second World War had a devastating effect on the economy and industrial bases in Europe and America, and when peace came, local demands for everyday consumption goods were mainly met by imported goods. The demand among less developed countries in Asia for industrial products grew rapidly, but they could not be supplied by Europe and America which were also suffered from serious destruction in factory and transportation facilities. Driven by the great demands in the export markets, Hong Kong seized the opportunity and resumed production very quickly.

Many factory owners returned to Hong Kong after the war to restart production, and despite the shortage of materials in the early days, in a few years, its manufacturing industries were already moving ahead. From the 972 registered factories in 1947, employing 51,338 workers, the numbers grew to 1,266 factories in 1948, and 81,571 workers. The scale and type of industries resumed to prewar condition. In 1947, shipbuilding and ship repairing hired 28% of registered workers and were the leading employers of industrial labour; they maintained this leading position until they were overtaken in 1950 by textiles industries. Nevertheless, the basis of Hong Kong’s economy remained its entrepot trade and in 1947, Hong Kong produced goods constituted only 10% of total export volume. -

Catalysts for Hong Kong’s industrialization: The China Factor

The drastic changes in China in the few years after the war stimulated the rapid growth of Hong Kong’s industry. The civil war in the mainland from 1946 and the change of government in 1949 led to an exodus of migrants into Hong Kong. The immigrants from different backgrounds bolstered Hong Kong’s manufacturing industry in different ways. From Shanghai, which had been the nation’s industrial centre before the war, over 30 leading cotton spinners arrived in Hong Kong between 1945 to 1950, bringing with them advance machinery, substantial capital and modern management and technological knowhow, and prompting the growth in Hong Kong of the spinning, weaving and garment industries.

The majority of postwar migrants came from Guangdong province where cities like Guangzhou and Shantou had had a good base of industry. Among these immigrants were experienced industrialists, and after arriving in Hong Kong, some of those who had been employees switched to start their own small-scale factories. They started up as cottage industries, resulting that a majority of small and medium enterprises was a feature of Hong Kong’s manufacturing industry. Many of the immigrants, however, were unskilled labourers, whose one hope in reaching Hong Kong was to find work and survival, regardless of how poor the factory conditions or how long the working hours. These people had been the pillar of Hong Kong’s industries.

-

Catalysts for Hong Kong’s Industrialization: The Korean War Embargo

The international scenarios shortly after the war also had significant impact upon Hong Kong’s industry. In 1951, a year after the Korea War broke out, the United Nations imposed a trade embargo on China, and Hong Kong as a British Colony adopted the UN’s resolution by restricting the export of strategic materials through Hong Kong to China, including rubber, plaster, petroleum products, some iron and steel products, transport equipment and machinery. The value of Hong Kong’s exports to China fell from 1.6 billion in 1951 to 0.182 billion in 1955.

The embargo hit Hong Kong’s economy very hard, the worst hit being the wharfing, cargo transportation, banking and insurance sectors. Under these circumstances, people turned to manufacturing as an alternative economic opportunity. Among them were those engaged in the re-export trade who were knowledgeable about markets that supplied raw materials and markets that demanded consumer products. By the mid-1950s, manufacturing had become a pillar of Hong Kong’s economy. In 1956, Hong Kong’s export value reached $3.21 billion, close to the level on the eve of the UN embargo ($3.71 billion), a proof that Hong Kong’s industries were making a significant contribution to the economy.

-

The Rise of New Industries Between the 1950s And 1960s

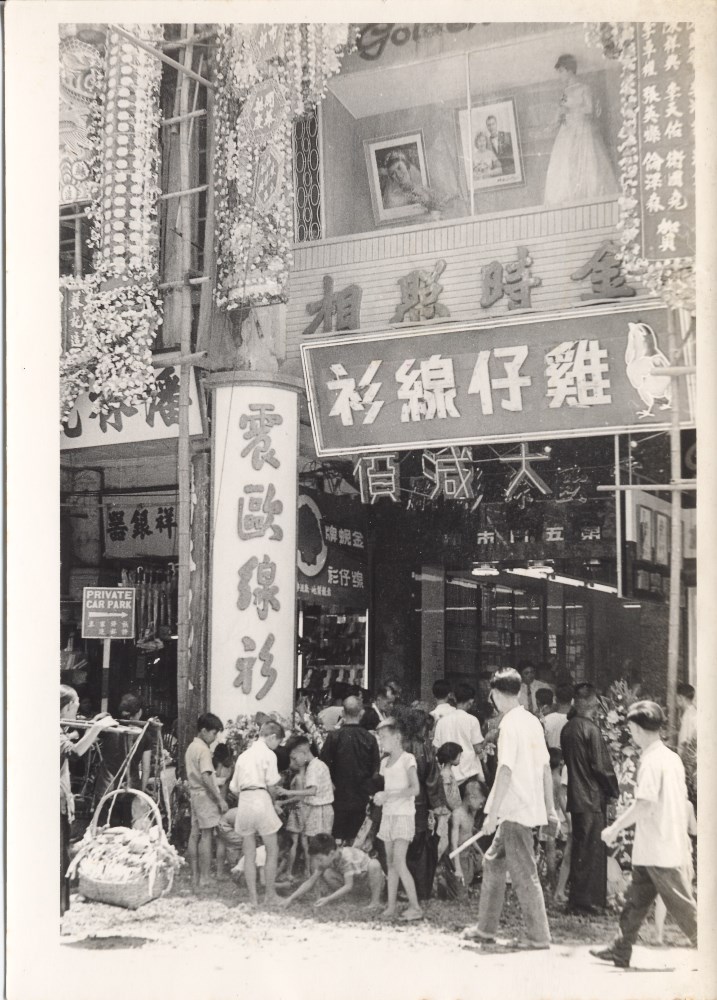

The types of industries after the war differed significantly from before. With the progress of technology and changes in lifestyle, the production of rubber products, torches and patent medicines which had dominated before the war gradually declined, and industries such as textiles, garments, plastics, watches and electronics took their places as pillars of the manufacturing sector. Some of the Shanghai industrialists established textile factories in Hong Kong, bringing with them new technologies in spinning and as a result, weaving, dyeing and finishing as well as garment-making also developed quickly, and an integrated, vertical production line of cotton goods arose.

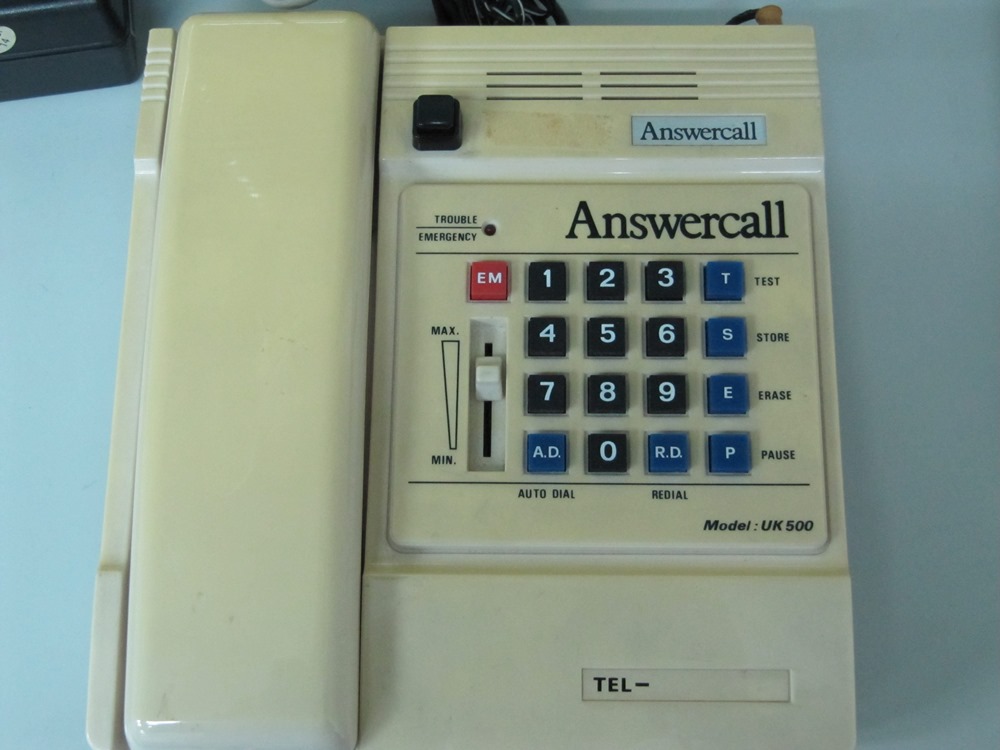

Plastics was a new raw material widely researched during the WWII and after the war, chemical enterprises in Europe and America supplied it to Hong Kong leading to the rise in the production of plastic toys, flowers, articles of everyday use, etc. When Switzerland and Germany relaxed the export of watch movements in the 1950s, a new line in the assembling of watch parts was born; in addition, the production of watch bands and watch cases took off as a result. In the 1960s, with a good number of American and Japanese companies setting up factories producing semiconductor radios, televisions, communication equipment and compact electronic parts in Hong Kong, the electronics industry blossomed.

-

From Processing and Assembling To Vertically Integrated Production

Hong Kong not only lacked raw materials for industrial development, it also lacked advanced technological knowhow so that its industries constantly remained at the processing and assembling levels. Between the 1960s and 1970s, industrialization took off and more production processes were in place. Take textiles as an example. Before the war, cotton weaving factories used cotton yarn imported from abroad, simple products like vests and socks were made. Fabrics woven in local factories were produced mainly for export and the local garment industry was still relatively undeveloped. After the war, the structure of the cotton industry became more integrated when a full, vertical line of production covering spinning, knitting and weaving, dyeing and finishing, garment design and making took place in Hong Kong.

Likewise, the production of plastics, metal wares, watches and electronics appeared as technology advanced so sophisticated component parts were made locally. As a result, enterprises began to integrate upstream and downstream production processes. However, for the main raw materials and state of the art technology, Hong Kong was still dependent on imports from overseas.

-

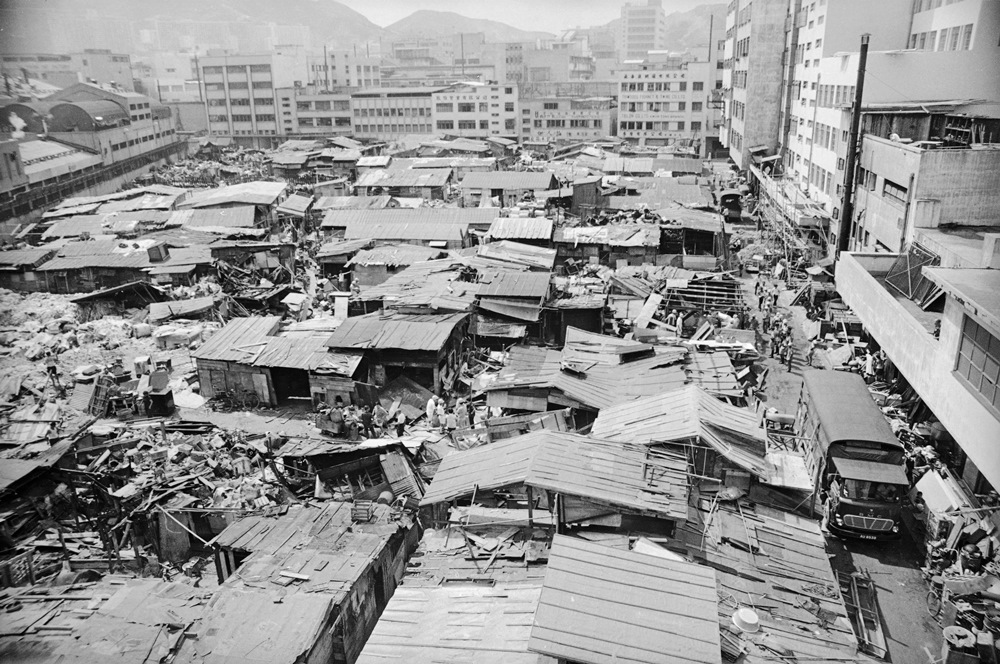

Cottage Industries in Tenement Buildings, Squatter Huts and Resettlement Buildings

Factories before the war were concentrated in old areas such as Shamshuipo, Mongkok, Kowloon City and the Western district. Small factories were located in the ground floor shops of tenement buildings, mingling with ordinary residences. Larger and better capitalised factories bought their own land to build stand alone factory premises that included plants, dormitories, wharfs, offices and retail outlets. After the war, factories sprang up in large numbers, many of them cottage industries. In the 1950s, some of the factory owners starting up with only several thousand dollars and unable to afford high rent, could only rent residential flats in tenement buildings. Frequently the front portion of the flat was used as the shop floor while the back was used as living space; the shop floor would be crammed and machinery and facilities simple; the operation of the factory depended on the owners’ family and a few employees.

Whereas plastics and metal factories requiring larger and heavier machinery were more often located in street shops, factories making garments which required smaller machines were set up on higher floors. Some small operators built very simple factories in squatter areas. In order to resettle small factories which were affected by demolition, the government built the first industrial resettlement buildings in Cheung Sha Wan in 1958. Since then, many more factory buildings were constructed close to resettlement areas and rented out cheaply so that small operators could continue their business. These included 6 or 7 storeyed Type H or Type I factory buildings.

-

The Formation of New Industrial Areas

With the rapid increase in population after the war, urban land became more expensive and pressure on land grew. The government began developing new towns in 1950 to supply cheaper lots for industries and housing. The new towns were created from large scale reclamation, providing cheap land for large factories to build up their facilities and multi-storeyed buildings for smaller enterprises. Low cost housing estates were built to make labour in proximity to industries. Kwun Tong and Tsuen Wan were the first to be developed, followed by Shatin and Tuen Mun.

New industrial areas were also opened up on the fringes of urban areas on Hong Kong Island and Kowloon. Industrial areas that emerged in the 1950s and 1960s included Cheung Sha Wan, Tai Kok Tsui, San Po Kong, Shau Kei Wan, Wong Chuk Hang and Chai Wan. Attracted by low land prices, easy transportation and nearness to cheap labour, different types of industries moved in. In the mid 1960s, the tender reserve price for Tai Yau Street, San Po Kong was only $6.00 per sq. ft; such cheap land made it very conducive to the development of labour-intensive industries such as garments and plastics. When the industrial estates in Tai Po and Yuen Long were completed in the 1970s and 1980s, many large enterprises were attracted to the New Territories.

-

Export-Oriented Light Industries

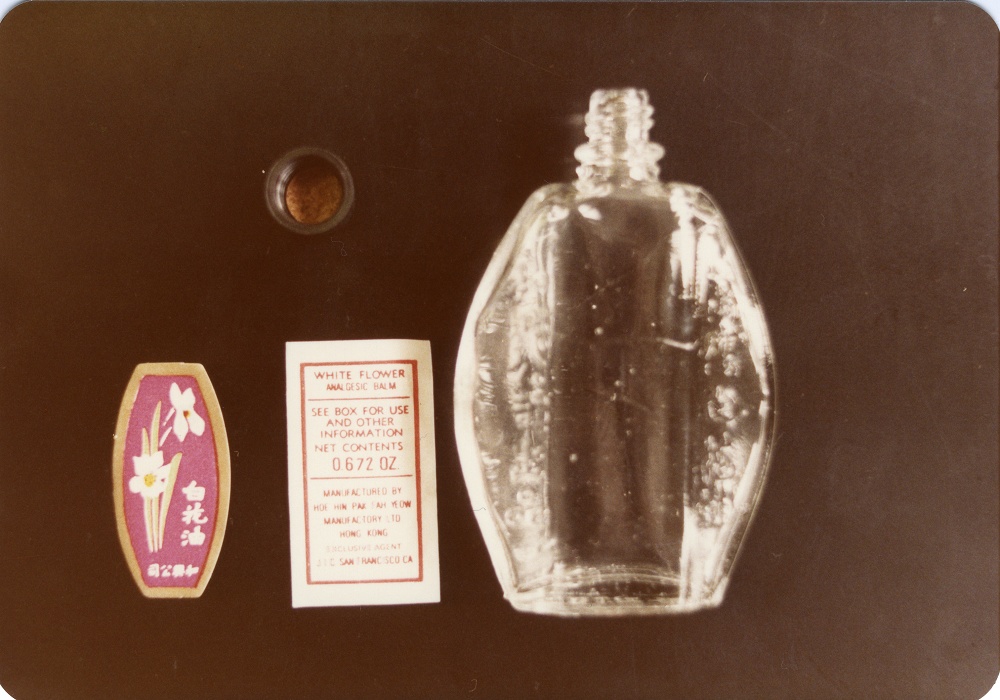

Hong Kong’s industry has always been dominated by export-oriented light industries. In the early years after the war, the main markets continued to be Southeast Asia and the British Commonwealth as before. Under the 1932 Ottawa Agreement, Hong Kong products were able to enter British territories on preferential tariff. Southeast Asian countries were the natural export markets of products from Hong Kong partly because of geographical proximity and partly the concentration of Chinese people there which gave Hong Kong Chinese producers a linguistic and cultural edge. Hong Kong-made shirts, patent medicines and articles for everyday use were widely sold.

Toward the late 1950s when markets in Europe and America began to open and Southeast Asian countries adopted a protectionist policy in order to nurture their own industries, Hong Kong producers reached out to markets in the West, relying on trading companies as intermediaries. By the mid 1960s, the United States had become the main destination of Hong Kong products with toys, garments, plastic flowers and wigs heading the list. In the 1970s, the larger Hong Kong factories collaborated with their American clients as Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM ) and the volume of export grew exponentially. In the late 1980s, Hong Kong manufacturers moved their production to the Mainland and developed the markets for their products there as well.

-

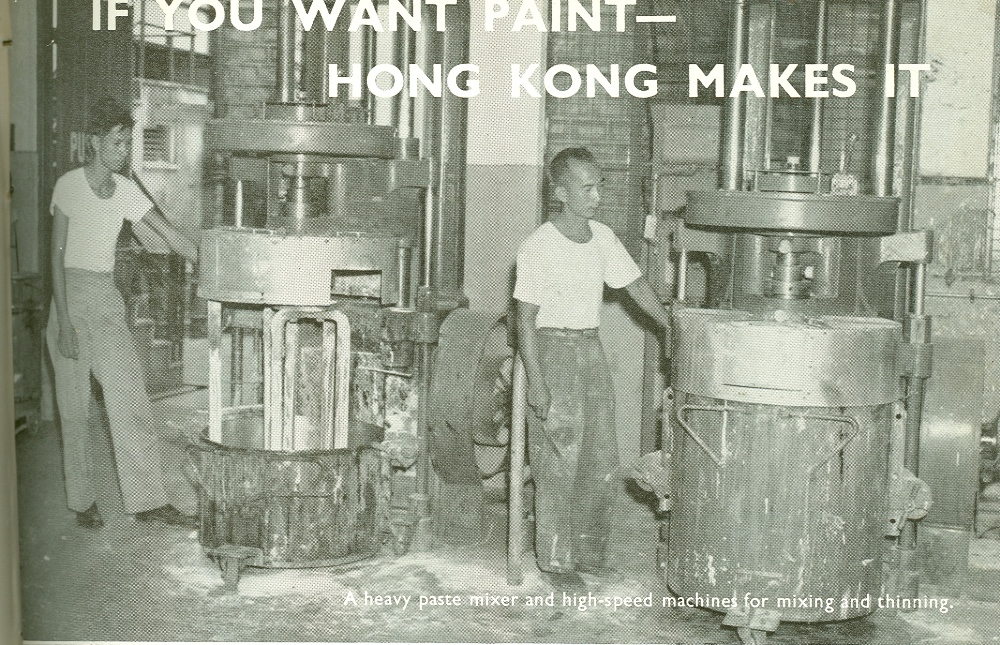

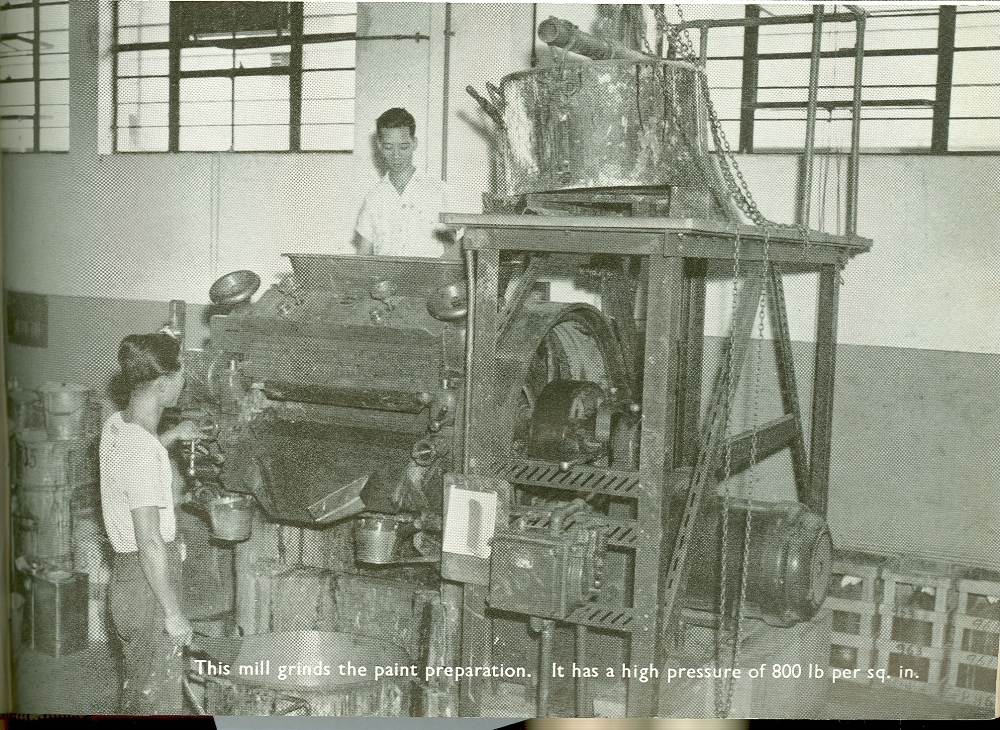

Local Market for Hong Kong Products

While Hong Kong’s industry had long been export-oriented, after the war, local firms also produced articles such as semi-finished goods, spare parts and component parts to support other factories. Factories within the same sector collaborated to form vertical production lines; the upstream producers supplied semi-finished or parts to downstream producers to create a continuous product line. In the textile sector for instance, spinning mills supplied yarn to weaving mills; weavers employed dyers to dye the fabrics they produced or to do final finishing before they could supply the finished fabric to garments factory for making into clothes.

Another example was the plastics industry: PVC factories supplied plastic film to factories that made handbags and swimming articles. Paint factories supplied paint for use in many different kinds of industries such as furniture, toys and electric fans; plastic factories supplied parts for garments, rattan ware and toys; electronics factories supplied parts for toys, watches and clocks and electrical appliances. In addition, the manufacturers of food, patent medicine and articles for daily use focused on local consumers, building up their own brand names to establish their market niche.

-

Producing for Consumers in Developed Countries

During the 20 years after the war, the economy of European countries and America moved toward developing tertiary industries, labour-intensive industries shifted toward Asia leading to the industrialization of developing countries. Established brands such as Mattel and Hasbro stopped production at home and started ordering their goods from low-cost regions, laying the foundation for Hong Kong’s emergence as the “toy kingdom” of Asia. In addition, Hong Kong’s light industries were greatly bolstered when Hallmark, Walmart and other major retailers opened up sourcing offices in Asia. Hong Kong’s manufacturers produced according to the designated design and style, a new mode called Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM).

In the following decades, the OEM mode of production prevailed, especially in the garments, electronics, plastics and watches. Typically, OEM meant large volume and stable orders, and, local factories were compelled to upgrade the standard of management and production in their factories in order to meet with the higher requirements of consumers in Europe and America. This resulted in the rise of standards in Hong Kong’s industry.

-

Dependence on Trading Companies as Intermediaries Before1980

Trading companies were the intermediaries between the local manufactures and clients in Europe and America. In the 1950s and 1960s, most of the local factories were too small to have a separate marketing department; the relative ignorance among factory operators of the commercial environment overseas combined with the language barrier made it inevitable for them to depend on trading companies for orders and sales. When trading firms received orders from overseas clients, they placed the orders on behalf of the clients with the factories which would produce accordingly. Sometimes manufacturers bought samples of articles, reproduced them and asked trading companies to sell them. Sometimes trading companies bought the goods from the factories and sold them to their clients overseas on their own accounts. In these cases, the profit could be considerable.

Some trading firms commonly known in Chinese as “zhuangkou” and ‘‘Indian Hongs’’ had specific trading partners. The former were operated by Chinese merchants and specialized in exporting goods to Southeast Asia; some of them even supplied credit to the manufacturers. ‘‘Indian Hongs’’ were run by South Asian merchants who focused on trade with the Middle East and African markets. In the 1980s when OEM were prevalent and as direct contact was made between local producers and overseas purchasers, trading companies declined.

-

Hong Kong Factories Relocated to Less Developed Regions In Search Of Preferential Tariff Treatment

As early as the 1950s, some of the larger local factories had moved part of their production overseas and became the pioneers in the relocation of industries. Due to preferential tariff, language and cultural reasons, Southeast Asia had long been a major market for Hong Kong products. When these countries declared independence one by one, they sought to nurture their own industries by restricting the import of Hong Kong goods. To sidestep such barriers, some Hong Kong factory owners moved their factories to these countries, producing and marketing their goods locally.

In addition, in the late 1950s, countries in Europe and America introduced quota systems to protect their own cotton industries which greatly restricted Hong Kong’s imports. The textile and garment industries which had mainly sold to European and American markets also moved their production to less developed territories such as Macao, Taiwan and even as far away as Cambodia, Burma, south Asia and Nigeria which were not subject to the quota system, and sold their products directly from there. Hong Kong businessmen preferred to work in former British territories since it was easier for the colonial government and British banks to obtain information about local conditions.

-

Moving Production Line to Pearl River Delta

By the 1970s Hong Kong’s industries were challenged by the skyrocketed land prices, a shortage of labour and the competition from nearby industrializing countries. With the Open Policy of China, Hong Kong capitalists started to invest on the mainland. In the early 1980s, local industries began to move north in order to enjoy cheaper land and labour, and for language and cultural reasons, Hong Kong capitalists concentrated their operations in the Pearl River Delta, with Shenzhen and Dongguan being the favourite localities. Between 1979 and 2005, 64.7 % of Guangdong Province’s foreign investment came from Hong Kong.

In the 1980s “custom manufacturing with materials, designs or samples supplied” and ‘compensation trade’ were the dominated investment modes. Hong Kong operators provided raw materials, equipment, technology and management while mainland operators provided land and labour. Finished products were taken back to Hong Kong for packing and export. The first industries to move to the mainland were labour-intensive ones, such as garments, plastics, watches and electronics. Upstream production which tends to be capital and technology intensive moved later, but when more downstream industries relocated northwards, raw materials providers such as paint and plastic materials were also compelled to follow in their footstep.

-

The Northward Exodus and the Transformation of Hong Kong’s Manufacturing

In the 1980s some factory operators were still skeptical about the investment environment of the mainland. The number of Hong Kong factories moving north grew exponentially in the 1990s. In 2009, some 90% of Guangdong’s Hong Kong’s enterprises had been established since the 1991, with 1996-2000 being the peak period. The 1990s saw the rapid spread of the ‘‘foreign invested enterprises’’ mode. Hong Kong businessmen expanded the scale of production, bought land for building factories and developed domestic sales. With cheaper land and wage cost these businessmen were able to increase their production as OEM, with the result that factories which had been medium sized in Hong Kong expanded their operations several folds once they moved to the mainland.

Factory operations in Hong Kong shrank throughout the 1990s, and workers were disbanded. The firms kept their offices in Hong Kong to receive orders and take care of banking, accounting, logistics and legal matters. In order to reduce costs, even some of these services were later moved north. The number of Hong Kong staff that was stationed on the mainland grew year on year, from 52,300 in 1988 to 237,500 in 2005. As the operation costs in the Pearl River Delta region continued to rise, the more labour intensive operations were in turn moved to other provinces, with the Yangzi delta being the main destination.

-

Road to Survival for Hong Kong’s Industry: OEM、ODM、OBM?

OEM has been a major mode of operation from the 1970s, most commonly applied in such consumer product industries as garments, electronics, plastics and watches. Hong Kong’s factories, collaborating with brand companies, large retailers from Europe and America, produced articles according to the specifications of the clients who then marketed the products themselves. In the 1980s, some of the factories tried to become ODM (Original Design Manufacturer) and OBM (Original Brand Manufacturers), setting up departments for research and development, design, marketing and sales. The designs were either sent to their own factories for production or outsourced to other factories as OEM.

The companies committed to ODM and OBM were mostly managed by the second generation entrepreneurs who had received western education and possessed professional knowledge in modern management. Some entrepreneurs believe that the brand companies will continue to depend on Hong Kong’s OEMs to supply their goods, making this a feasible option for Hong Kong operators in the long-term. ODM and OBM, on the other hand, requires the Hong Kong operator to set up their own retail networks and maintain the brand status themselves which cannot be done without large financial backing, something that not many medium and small-sized enterprises can afford.

-

What Was the Role of the Government in Industry?

Hong Kong government used to adopt laissez-faire policy and take on a passive role. The Commerce and Industry Department was formed in 1949 to give advice on new industries and to promote Hong Kong products to overseas markets. The major function of the government in industry was to provide industrial land. Through town planning and land auction policies, industrial enterprises were arranged or attracted to new industrial lands.

In addition, the government assigned different functions of promoting industries through statutory bodies like the Federation of Hong Kong Industries (established in 1960), The Trade Development Council (established in 1966), The Hong Kong Productivity Council (established in 1967), as well as The Vocational Training Council (established in 1982). Through visits to other countries, local and overseas exhibitions, exchanges and seminars, publicity, technical education, information dissemination, etc., these institutions provided facilitative measures to local industries. The effectiveness of these activities was always in dispute, especially when the direction and future of Hong Kong’s industries were under heat discussion. One thing we can be sure is that the government of Hong Kong is never as active as the other governments in the East Asian region such as South Korea and Taiwan.

Copyright © 2012 Hong Kong Memory. All rights reserved. -