A Compassionate Soul: The Human Art Club Years (1945-1949)

“We are members of the world. We love this world. All we create belongs to this world of the people.”

── Declaration of the Establishment of the Human Art Club, 1946

The Japanese surrendered in September 1945, but the situation in the mainland remained very unstable. As a result, many mainland scholars and artists fled to Hong Kong in quick succession. Huang Xinbo was among those who arrived, working as a journalist at the Chinese Business Daily. With the support of the cultural community, Huang and his friends established Human Art Club and Human Publishing House in 1946. Not only did these provide a platform for artists and scholars to discuss issues related to art, they also acted as a support group during this difficult time. Actively promoting art and cultural activities through exhibitions and publications, their contributions highly influenced the development of arts and culture in post-war Hong Kong.

As a journalist, Huang Xinbo was in frequent contact with people from all walks of life, cultivating a profound understanding of their living conditions. Their plight became his inspiration. Huang not only continued the rich lyrical style which he developed when he was in Guilin, but also added his own penetrating life observations. In 1947, four primary school students were shot and killed while accidentally crossing the border between the mainland and the New Territories, around the Sheng Shui area. In grief and outrage, Huang created an emotionally charged work, Accusation (1947). This work depicts the children, naked, bleeding and fists tightly clenched, slumped over the arms of an old woman who has become numb with grief.

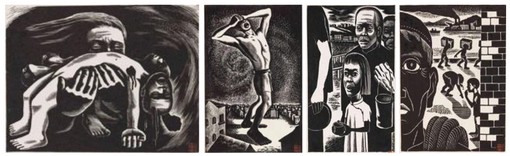

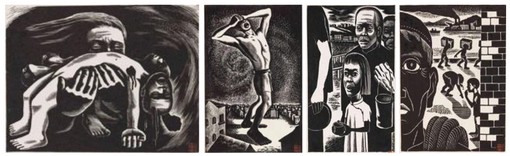

Structuring the images with a meticulous application of black and white tones, Huang Xinbo’s simple but refined shapes highlight and reflect the lives of the working class in Hong Kong during the early post-war period. Life in Hong Kong was difficult at the time. People suffered from low wages and high unemployment as many factories went bankrupt. After Selling His Blood (1948) depicts an unemployed man forced to sell his blood for a living. In agony, he experiences vertigo after undergoing the unpleasant process. In another work, Scene at Happy Valley, Hong Kong (1948), the background of the horse racecourse in Happy Valley is framed by the high-end residential houses and flats of the upper-class district. In the foreground, the poor queue for a charity meal given out by the wealthy. The elderly and young children hold out their bowls waiting for food, with expressionless faces, displaying the world-weariness of the starving poor. Having worked near a wharf in the Western District, Huang created At the Wharf (1948) drawing on his own observations – the pier is packed with hardworking coolies and homeless children. At the time, society provided no labour benefits or employment protection. Working hours were long and wages were low, offering no hope of escaping lifelong hardship. Brimming with affection and empathy, Huang’s woodcuts from this period serve as valuable testament to post-war Hong Kong society.

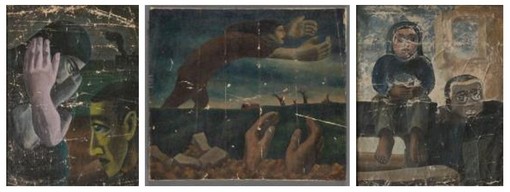

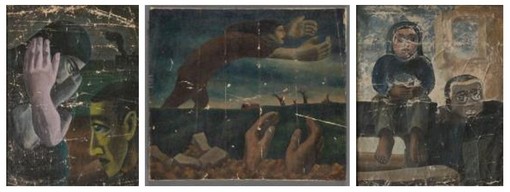

Having studied Western painting at the Shanghai Art Academy, Huang Xinbo had always aspired to be an oil painter. During his time in Hong Kong between 1946 and 1948, he created some 20 oil paintings. Following closely on Western trends in modern painting at the time, Huang was interested in a variety of styles ranging from the classicism to the modernism. He frequented foreign bookstores to study the catalogues of prominent Western painters; some of the works he particularly admired were those of Ben Shahn’s (1898-1969), an American socialist realist painter. Shahn gave voice to those suffering from persecution and probed the issue of injustice in modern city life through his paintings. Huang greatly appreciated the application of Shahn’s unique symbolism on the depiction of the inner worlds of his characters. Incorporating Shahn’s style in his work, Huang placed emphasis on the symbolic and psychological portrayal of his characters by projecting subjective emotions on objective imagery. City People (1946) and Seeds (1947) both depict the inner feelings of the subjects in an overstated manner; the partially magnified pairs of hands stimulate the viewers’ emotions and empathy towards the characters’ distress. In another work, Ruins (1947), two children are shown glancing around amidst the debris after a battle. The girl, holding an empty can, is depicted in silence and expectation of a better tomorrow.

Huang Xinbo’s experimental style was not accepted by the artistic circle, even though his works expressed his compassion for the suffering. His peers believed that Huang leaned on formalism, creating works without combative strength or courage. In the spring of 1948, the Human Art Club held a meeting criticising the artistic ideology in his oil paintings. Despite the criticism, Huang went on to create a further ten oil paintings following a similar style. In 1949, the Hong Kong Yan Press published Art Album of Xinbo, featuring 33 of his works, including 18 oil paintings. However, the real copy of those paintings is hardly to be seen at nowadays.

A Compassionate Soul: The Human Art Club Years (1945-1949)

“We are members of the world. We love this world. All we create belongs to this world of the people.”

── Declaration of the Establishment of the Human Art Club, 1946

The Japanese surrendered in September 1945, but the situation in the mainland remained very unstable. As a result, many mainland scholars and artists fled to Hong Kong in quick succession. Huang Xinbo was among those who arrived, working as a journalist at the Chinese Business Daily. With the support of the cultural community, Huang and his friends established Human Art Club and Human Publishing House in 1946. Not only did these provide a platform for artists and scholars to discuss issues related to art, they also acted as a support group during this difficult time. Actively promoting art and cultural activities through exhibitions and publications, their contributions highly influenced the development of arts and culture in post-war Hong Kong.

As a journalist, Huang Xinbo was in frequent contact with people from all walks of life, cultivating a profound understanding of their living conditions. Their plight became his inspiration. Huang not only continued the rich lyrical style which he developed when he was in Guilin, but also added his own penetrating life observations. In 1947, four primary school students were shot and killed while accidentally crossing the border between the mainland and the New Territories, around the Sheng Shui area. In grief and outrage, Huang created an emotionally charged work, Accusation (1947). This work depicts the children, naked, bleeding and fists tightly clenched, slumped over the arms of an old woman who has become numb with grief.

Structuring the images with a meticulous application of black and white tones, Huang Xinbo’s simple but refined shapes highlight and reflect the lives of the working class in Hong Kong during the early post-war period. Life in Hong Kong was difficult at the time. People suffered from low wages and high unemployment as many factories went bankrupt. After Selling His Blood (1948) depicts an unemployed man forced to sell his blood for a living. In agony, he experiences vertigo after undergoing the unpleasant process. In another work, Scene at Happy Valley, Hong Kong (1948), the background of the horse racecourse in Happy Valley is framed by the high-end residential houses and flats of the upper-class district. In the foreground, the poor queue for a charity meal given out by the wealthy. The elderly and young children hold out their bowls waiting for food, with expressionless faces, displaying the world-weariness of the starving poor. Having worked near a wharf in the Western District, Huang created At the Wharf (1948) drawing on his own observations – the pier is packed with hardworking coolies and homeless children. At the time, society provided no labour benefits or employment protection. Working hours were long and wages were low, offering no hope of escaping lifelong hardship. Brimming with affection and empathy, Huang’s woodcuts from this period serve as valuable testament to post-war Hong Kong society.

Having studied Western painting at the Shanghai Art Academy, Huang Xinbo had always aspired to be an oil painter. During his time in Hong Kong between 1946 and 1948, he created some 20 oil paintings. Following closely on Western trends in modern painting at the time, Huang was interested in a variety of styles ranging from the classicism to the modernism. He frequented foreign bookstores to study the catalogues of prominent Western painters; some of the works he particularly admired were those of Ben Shahn’s (1898-1969), an American socialist realist painter. Shahn gave voice to those suffering from persecution and probed the issue of injustice in modern city life through his paintings. Huang greatly appreciated the application of Shahn’s unique symbolism on the depiction of the inner worlds of his characters. Incorporating Shahn’s style in his work, Huang placed emphasis on the symbolic and psychological portrayal of his characters by projecting subjective emotions on objective imagery. City People (1946) and Seeds (1947) both depict the inner feelings of the subjects in an overstated manner; the partially magnified pairs of hands stimulate the viewers’ emotions and empathy towards the characters’ distress. In another work, Ruins (1947), two children are shown glancing around amidst the debris after a battle. The girl, holding an empty can, is depicted in silence and expectation of a better tomorrow.

Huang Xinbo’s experimental style was not accepted by the artistic circle, even though his works expressed his compassion for the suffering. His peers believed that Huang leaned on formalism, creating works without combative strength or courage. In the spring of 1948, the Human Art Club held a meeting criticising the artistic ideology in his oil paintings. Despite the criticism, Huang went on to create a further ten oil paintings following a similar style. In 1949, the Hong Kong Yan Press published Art Album of Xinbo, featuring 33 of his works, including 18 oil paintings. However, the real copy of those paintings is hardly to be seen at nowadays.