Did pre-war Hong Kong have industries?

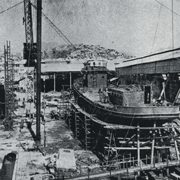

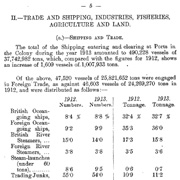

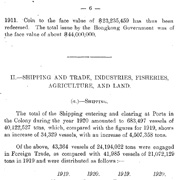

Shipbuilding and Ship RepairingShip repairing and shipbuilding emerged as major industries as Hong Kong evolved into a commercial and shipping centre. Facilities were simple until John Lamont built a dry dock in Aberdeen in 1857. In 1863, several British firms formed the Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock Company by combining some of the existing docks, including Lamont’s. The company, concentrating its operations in Hunghom from 1880, grew into the largest industrial enterprise in East Asia. The opening of the Taikoo Dockyard and Engineering Company at Quarry Bay in 1907 further enhanced Hong Kong’s shipbuilding capacity. Dockyards operated by Chinese companies included Kwong Hip Lung (established 1877), Ah King’s Slipway (1891) and Tung Hing Loong (around 1897). |

Sugar RefiningSugar refining was another major early industry in Hong Kong. The China Sugar Refinery, operated by Jardine, Matheson & Co., and Taikoo Sugar Refinery, operated by Butterfield & Swire, were the two largest establishments in the 19th century. Hong Kong’s white, refined sugar, was particularly popular in China, Canada, Australia and the United States in the 19th century and it found new markets in India and the Persian Gulf in the early 20th century. |

Chinese ManufacturesApart from the building of small boats, early Chinese-owned industries also included handicrafts such as the making of rattan ware, preserved ginger and fruits. From the early 20th century, Chinese entrepreneurs began investing in a wide range of new industries. The fastest growing one was textile industry, which produced cotton piece goods, knitted vests, socks and silk products. Other important products were furniture, flash lights and battery, and rubber shoes. The processing of metal such as tin and copper was also common. The Chinese Manufacturers’ Union was founded in 1934 to promote Chinese industries and find overseas markets for their goods. This was a good indicator of the prosperity of Chinese manufactures. |

A Traditional Industry – Preserving GingerPreserving ginger, one of Hong Kong’s best known traditional light industries, originated with a Chinese man named Lee. Lee started his career by selling ginger and other pickled foods at a street stall in Guangzhou, and the story goes that one day, an Englishman brought home to England some ginger bought from his stall and it became so popular that he was inundated by orders from England. To meet the demand, Lee founded the Chai Lung ginger factory with two friends, which was later relocated it to Hong Kong in 1846. By 1900, the better known ginger factories in Hong Kong also included Choy Fong's Ginger Factory (翠芳糖薑廠) and Man Loong Ginger Factory (民隆糖薑廠). During the busy seasons, these factories employed over a hundred workers each. Young ginger was imported from Guangzhou, which were then processed and packaged before being exported to markets in Europe, the United States and Australia. In 1937, Hong Kong Exporters Association (香港糖薑經銷商會) was founded to promote new favour, improve packaging and seek new markets. |

1904 – Hong Kong’s First Chinese Textile Factory OpenedHong Kong’s first knitting and weaving factory was founded in 1904 by Chinese investors. Many other Chinese-operated factories followed, the best known being Li Man Hing Kwok, Chow Ngai Hing and Dongya. These factories produced cotton knitted cloth, and in the early days, large factories also turned knitted cloth into cotton vests and socks for the local market. From the 1910s, Hong Kong’s cotton textiles began to compete with Japanese products. In the following decade, Hong Kong enhanced its competitiveness by using more advanced machinery and, as a result, was able to supply not only the local market but also overseas markets such as China and Australia. |

Hong Kong’s Manufactures were Made for ExportHong Kong’s Manufactures were Made for ExportThe majority of Hong Kong’s products were made for export. For many years North China was the largest market for refined sugar followed by India. Preserved ginger fed markets in Britain, Australia, Holland and the United States. Under the Imperial Preference system, knitted piece-goods, electric torches and batteries, and rubber shoes and boots were exported to different places within the British Empire such as India, Malaya, Ceylon, the West Indies and Britain itself, while knitted vests and socks were exported to the West Indies, the Straits Settlements, Malaya and India. Lower-grade knitted goods were sold outside the Empire to South China, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. |

China’s Political Conditions Affected Hong Kong IndustriesBecause of its export-oriented character, the development of Hong Kong’s industries was greatly affected by external factors. The Chinese Revolution of 1911, for instance, and the subsequent political unrest that swept the country had far-reaching repercussions. The effects, however, were uneven. Industries that relied on the China market, such as sugar refining, were badly hit, yet the anti-Japanese boycott in the latter part of 1919 stimulated demand for Hong Kong sugar. Some industries benefitted directly from the chaos. The extraordinary demand for military equipment in China boosted the manufacturing of leather and hides. When there was a decline in the export of certain products, such as vinegar, lard and Chinese spirits from China, local manufacturers gained a larger share of the market by stepping up production to make up the short fall. |

Effects of the First World WarThe First World War of 1914-1918 also affected Hong Kong’s industries in a variety of ways. The overall disruption of European shipping, scarcity of tonnage, rise in freight and shrunken demand for consumer goods in Europe had a generally adverse effect. Products that depended primarily on the European market such as rattan furniture, preserved ginger and preserved fruits fell drastically. Shipbuilding and rope making also suffered. Sugar-refining was hit from time to time by the very high price of raw sugar, yet Hong Kong’s refined sugars were able to find new and valuable markets in India and the Persian Gulf. When the export of cement from Germany discontinued, Australia turned to Hong Kong for supply and the industry did well throughout the war years. After the War, many products resumed pre-war levels. The quickest recovery was made by rattan furniture which jumped in export value from $10,000 in 1918 to $380,000 in 1919. |

Industrial Development in the 1930sThe 1930s saw much development in Chinese-owned industries. One significant change that boosted Hong Kong’s industries was the Imperial Preference Policy. Imperial Preference allowed products made in British Colony to enjoy preferential tariff treatment when exported to other parts of the British Empire. In Hong Kong, this stimulated the production of rubber shoes, electric torches and batteries, preserved ginger, cotton knitted goods and silk products. |

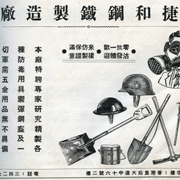

The Japanese Invasion of ChinaIronically, the Japanese invasion of China which started in 1937 boosted Hong Kong’s industrial development. Hostilities in China caused many industrialists to relocate their factories to Hong Kong and industries hitherto unknown in the colony came into being. The manufacture of war necessities, such as paint, gas masks, metal helmets, spade and entrenching tools, uniforms and water-bottles, as well as the assembling of field telephones and portable transmitting and receiving sets, grew quickly. |

Industrial EmploymentIn the 19th century, many more workers were engaged in the service sector than in manufacturing. Fewer than 6,800 persons were recorded as being employed in manufacturing in the 1870s. The number climbed to 91,000 in 1921, when the census report shows that many were employed in new industries such as clothing (27.5%), furniture and rattan ware (22.2%) and metal processing (20.6%). By 1931, the number had grown to 100,088, with textiles, clothing, furniture, construction materials and metal refining industries continuing to be the main employers. Notably, many women worked in factories making rubber shoes and boots. |

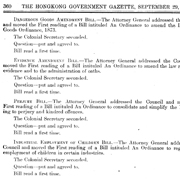

Labour LegislationThere was no law to regulate industrial employment or factory premises until the 1920s. In 1922 the Industrial Employment of Children Ordinance was enacted, not to limit the age of children working in factories but only to propose the minimum age for different jobs, e.g. children under 15 were not to work in dangerous industries. The Factory (Accidents) Ordinance followed in 1927, which governed the registration and safety operation of factories and workshops. In 1929, the Industrial Employment of Women, Young Persons and Children Amendment Ordinance was passed, barring female workers and young persons from being employed in certain dangerous industries and during specified hours in the evening. The last two ordinances were consolidated into a new one in 1932, which became the basis of legislation governing employment and factory safety in Hong Kong from the 1930s through the Second World War to the 1960s. |

Strikes and Labour MovementsAs industry developed, so did labour movements. While strikes among industrial workers broke out from time to time, none had a bigger impact than the General Strike of 1925, which was followed by a boycott of British shipping and trade in South China. The Strike and Boycott almost paralysed production of every kind in Hong Kong. After this, some unions were labelled as communist and a number of agitators were deported from Hong Kong. In the 1930s, far fewer strikes occurred. |

Hong Kong’s Pre-war Industrial Development – A ReviewBy 1941, just before the Japanese Occupation, when factories were either shut down or confiscated, Hong Kong had built up a flourishing export trade in locally- manufactured goods to China, the neighbouring regions, the British Empire and other distant parts of the world. Not only did it defy the imperial scheme of things by expanding its role beyond a commercial port to that of an industrial centre, it was even competing with British manufactures in a few items in the British home market – the early signs of a phenomenon that was to stun the world in the 1960s and 70s. Since the classic colony was one that exported raw materials and imported manufactured products from Britain, Hong Kong enjoyed a very special status in the British and world history by becoming an industrial colony. |

- {{0+1}}

- {{1+1}}

- {{2+1}}

- {{3+1}}

- {{4+1}}

- {{5+1}}

- {{6+1}}

- {{7+1}}

- {{8+1}}

- {{9+1}}

- {{10+1}}

- {{11+1}}

- {{12+1}}

- {{13+1}}

- {{14+1}}

- {{15+1}}

- {{16+1}}

Shipbuilding and Ship RepairingShip repairing and shipbuilding emerged as major industries as Hong Kong evolved into a commercial and shipping centre. Facilities were simple until John Lamont built a dry dock in Aberdeen in 1857. In 1863, several British firms formed the Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock Company by combining some of the existing docks, including Lamont’s. The company, concentrating its operations in Hunghom from 1880, grew into the largest industrial enterprise in East Asia. The opening of the Taikoo Dockyard and Engineering Company at Quarry Bay in 1907 further enhanced Hong Kong’s shipbuilding capacity. Dockyards operated by Chinese companies included Kwong Hip Lung (established 1877), Ah King’s Slipway (1891) and Tung Hing Loong (around 1897). |

Sugar RefiningSugar refining was another major early industry in Hong Kong. The China Sugar Refinery, operated by Jardine, Matheson & Co., and Taikoo Sugar Refinery, operated by Butterfield & Swire, were the two largest establishments in the 19th century. Hong Kong’s white, refined sugar, was particularly popular in China, Canada, Australia and the United States in the 19th century and it found new markets in India and the Persian Gulf in the early 20th century. |

Chinese ManufacturesApart from the building of small boats, early Chinese-owned industries also included handicrafts such as the making of rattan ware, preserved ginger and fruits. From the early 20th century, Chinese entrepreneurs began investing in a wide range of new industries. The fastest growing one was textile industry, which produced cotton piece goods, knitted vests, socks and silk products. Other important products were furniture, flash lights and battery, and rubber shoes. The processing of metal such as tin and copper was also common. The Chinese Manufacturers’ Union was founded in 1934 to promote Chinese industries and find overseas markets for their goods. This was a good indicator of the prosperity of Chinese manufactures. |

A Traditional Industry – Preserving GingerPreserving ginger, one of Hong Kong’s best known traditional light industries, originated with a Chinese man named Lee. Lee started his career by selling ginger and other pickled foods at a street stall in Guangzhou, and the story goes that one day, an Englishman brought home to England some ginger bought from his stall and it became so popular that he was inundated by orders from England. To meet the demand, Lee founded the Chai Lung ginger factory with two friends, which was later relocated it to Hong Kong in 1846. By 1900, the better known ginger factories in Hong Kong also included Choy Fong's Ginger Factory (翠芳糖薑廠) and Man Loong Ginger Factory (民隆糖薑廠). During the busy seasons, these factories employed over a hundred workers each. Young ginger was imported from Guangzhou, which were then processed and packaged before being exported to markets in Europe, the United States and Australia. In 1937, Hong Kong Exporters Association (香港糖薑經銷商會) was founded to promote new favour, improve packaging and seek new markets. |

1904 – Hong Kong’s First Chinese Textile Factory OpenedHong Kong’s first knitting and weaving factory was founded in 1904 by Chinese investors. Many other Chinese-operated factories followed, the best known being Li Man Hing Kwok, Chow Ngai Hing and Dongya. These factories produced cotton knitted cloth, and in the early days, large factories also turned knitted cloth into cotton vests and socks for the local market. From the 1910s, Hong Kong’s cotton textiles began to compete with Japanese products. In the following decade, Hong Kong enhanced its competitiveness by using more advanced machinery and, as a result, was able to supply not only the local market but also overseas markets such as China and Australia. |

Hong Kong’s Manufactures were Made for ExportHong Kong’s Manufactures were Made for ExportThe majority of Hong Kong’s products were made for export. For many years North China was the largest market for refined sugar followed by India. Preserved ginger fed markets in Britain, Australia, Holland and the United States. Under the Imperial Preference system, knitted piece-goods, electric torches and batteries, and rubber shoes and boots were exported to different places within the British Empire such as India, Malaya, Ceylon, the West Indies and Britain itself, while knitted vests and socks were exported to the West Indies, the Straits Settlements, Malaya and India. Lower-grade knitted goods were sold outside the Empire to South China, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. |

China’s Political Conditions Affected Hong Kong IndustriesBecause of its export-oriented character, the development of Hong Kong’s industries was greatly affected by external factors. The Chinese Revolution of 1911, for instance, and the subsequent political unrest that swept the country had far-reaching repercussions. The effects, however, were uneven. Industries that relied on the China market, such as sugar refining, were badly hit, yet the anti-Japanese boycott in the latter part of 1919 stimulated demand for Hong Kong sugar. Some industries benefitted directly from the chaos. The extraordinary demand for military equipment in China boosted the manufacturing of leather and hides. When there was a decline in the export of certain products, such as vinegar, lard and Chinese spirits from China, local manufacturers gained a larger share of the market by stepping up production to make up the short fall. |

Effects of the First World WarThe First World War of 1914-1918 also affected Hong Kong’s industries in a variety of ways. The overall disruption of European shipping, scarcity of tonnage, rise in freight and shrunken demand for consumer goods in Europe had a generally adverse effect. Products that depended primarily on the European market such as rattan furniture, preserved ginger and preserved fruits fell drastically. Shipbuilding and rope making also suffered. Sugar-refining was hit from time to time by the very high price of raw sugar, yet Hong Kong’s refined sugars were able to find new and valuable markets in India and the Persian Gulf. When the export of cement from Germany discontinued, Australia turned to Hong Kong for supply and the industry did well throughout the war years. After the War, many products resumed pre-war levels. The quickest recovery was made by rattan furniture which jumped in export value from $10,000 in 1918 to $380,000 in 1919. |

Industrial Development in the 1930sThe 1930s saw much development in Chinese-owned industries. One significant change that boosted Hong Kong’s industries was the Imperial Preference Policy. Imperial Preference allowed products made in British Colony to enjoy preferential tariff treatment when exported to other parts of the British Empire. In Hong Kong, this stimulated the production of rubber shoes, electric torches and batteries, preserved ginger, cotton knitted goods and silk products. |

The Japanese Invasion of ChinaIronically, the Japanese invasion of China which started in 1937 boosted Hong Kong’s industrial development. Hostilities in China caused many industrialists to relocate their factories to Hong Kong and industries hitherto unknown in the colony came into being. The manufacture of war necessities, such as paint, gas masks, metal helmets, spade and entrenching tools, uniforms and water-bottles, as well as the assembling of field telephones and portable transmitting and receiving sets, grew quickly. |

Industrial EmploymentIn the 19th century, many more workers were engaged in the service sector than in manufacturing. Fewer than 6,800 persons were recorded as being employed in manufacturing in the 1870s. The number climbed to 91,000 in 1921, when the census report shows that many were employed in new industries such as clothing (27.5%), furniture and rattan ware (22.2%) and metal processing (20.6%). By 1931, the number had grown to 100,088, with textiles, clothing, furniture, construction materials and metal refining industries continuing to be the main employers. Notably, many women worked in factories making rubber shoes and boots. |

Labour LegislationThere was no law to regulate industrial employment or factory premises until the 1920s. In 1922 the Industrial Employment of Children Ordinance was enacted, not to limit the age of children working in factories but only to propose the minimum age for different jobs, e.g. children under 15 were not to work in dangerous industries. The Factory (Accidents) Ordinance followed in 1927, which governed the registration and safety operation of factories and workshops. In 1929, the Industrial Employment of Women, Young Persons and Children Amendment Ordinance was passed, barring female workers and young persons from being employed in certain dangerous industries and during specified hours in the evening. The last two ordinances were consolidated into a new one in 1932, which became the basis of legislation governing employment and factory safety in Hong Kong from the 1930s through the Second World War to the 1960s. |

Strikes and Labour MovementsAs industry developed, so did labour movements. While strikes among industrial workers broke out from time to time, none had a bigger impact than the General Strike of 1925, which was followed by a boycott of British shipping and trade in South China. The Strike and Boycott almost paralysed production of every kind in Hong Kong. After this, some unions were labelled as communist and a number of agitators were deported from Hong Kong. In the 1930s, far fewer strikes occurred. |

Hong Kong’s Pre-war Industrial Development – A ReviewBy 1941, just before the Japanese Occupation, when factories were either shut down or confiscated, Hong Kong had built up a flourishing export trade in locally- manufactured goods to China, the neighbouring regions, the British Empire and other distant parts of the world. Not only did it defy the imperial scheme of things by expanding its role beyond a commercial port to that of an industrial centre, it was even competing with British manufactures in a few items in the British home market – the early signs of a phenomenon that was to stun the world in the 1960s and 70s. Since the classic colony was one that exported raw materials and imported manufactured products from Britain, Hong Kong enjoyed a very special status in the British and world history by becoming an industrial colony. |

- {{0 + 1}}

- {{1 + 1}}

- {{2 + 1}}

- {{3 + 1}}

- {{4 + 1}}

- {{5 + 1}}

- {{6 + 1}}

- {{7 + 1}}

- {{8 + 1}}

- {{9 + 1}}

- {{10 + 1}}

- {{11 + 1}}

- {{12 + 1}}

- {{13 + 1}}

- {{14 + 1}}

- {{15 + 1}}

- {{16 + 1}}

Did pre-war Hong Kong have industries?

Shipbuilding and Ship RepairingShip repairing and shipbuilding emerged as major industries as Hong Kong evolved into a commercial and shipping centre. Facilities were simple until John Lamont built a dry dock in Aberdeen in 1857. In 1863, several British firms formed the Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock Company by combining some of the existing docks, including Lamont’s. The company, concentrating its operations in Hunghom from 1880, grew into the largest industrial enterprise in East Asia. The opening of the Taikoo Dockyard and Engineering Company at Quarry Bay in 1907 further enhanced Hong Kong’s shipbuilding capacity. Dockyards operated by Chinese companies included Kwong Hip Lung (established 1877), Ah King’s Slipway (1891) and Tung Hing Loong (around 1897). |

Sugar RefiningSugar refining was another major early industry in Hong Kong. The China Sugar Refinery, operated by Jardine, Matheson & Co., and Taikoo Sugar Refinery, operated by Butterfield & Swire, were the two largest establishments in the 19th century. Hong Kong’s white, refined sugar, was particularly popular in China, Canada, Australia and the United States in the 19th century and it found new markets in India and the Persian Gulf in the early 20th century. |

Chinese ManufacturesApart from the building of small boats, early Chinese-owned industries also included handicrafts such as the making of rattan ware, preserved ginger and fruits. From the early 20th century, Chinese entrepreneurs began investing in a wide range of new industries. The fastest growing one was textile industry, which produced cotton piece goods, knitted vests, socks and silk products. Other important products were furniture, flash lights and battery, and rubber shoes. The processing of metal such as tin and copper was also common. The Chinese Manufacturers’ Union was founded in 1934 to promote Chinese industries and find overseas markets for their goods. This was a good indicator of the prosperity of Chinese manufactures. |

A Traditional Industry – Preserving GingerPreserving ginger, one of Hong Kong’s best known traditional light industries, originated with a Chinese man named Lee. Lee started his career by selling ginger and other pickled foods at a street stall in Guangzhou, and the story goes that one day, an Englishman brought home to England some ginger bought from his stall and it became so popular that he was inundated by orders from England. To meet the demand, Lee founded the Chai Lung ginger factory with two friends, which was later relocated it to Hong Kong in 1846. By 1900, the better known ginger factories in Hong Kong also included Choy Fong's Ginger Factory (翠芳糖薑廠) and Man Loong Ginger Factory (民隆糖薑廠). During the busy seasons, these factories employed over a hundred workers each. Young ginger was imported from Guangzhou, which were then processed and packaged before being exported to markets in Europe, the United States and Australia. In 1937, Hong Kong Exporters Association (香港糖薑經銷商會) was founded to promote new favour, improve packaging and seek new markets. |

1904 – Hong Kong’s First Chinese Textile Factory OpenedHong Kong’s first knitting and weaving factory was founded in 1904 by Chinese investors. Many other Chinese-operated factories followed, the best known being Li Man Hing Kwok, Chow Ngai Hing and Dongya. These factories produced cotton knitted cloth, and in the early days, large factories also turned knitted cloth into cotton vests and socks for the local market. From the 1910s, Hong Kong’s cotton textiles began to compete with Japanese products. In the following decade, Hong Kong enhanced its competitiveness by using more advanced machinery and, as a result, was able to supply not only the local market but also overseas markets such as China and Australia. |

Hong Kong’s Manufactures were Made for ExportHong Kong’s Manufactures were Made for ExportThe majority of Hong Kong’s products were made for export. For many years North China was the largest market for refined sugar followed by India. Preserved ginger fed markets in Britain, Australia, Holland and the United States. Under the Imperial Preference system, knitted piece-goods, electric torches and batteries, and rubber shoes and boots were exported to different places within the British Empire such as India, Malaya, Ceylon, the West Indies and Britain itself, while knitted vests and socks were exported to the West Indies, the Straits Settlements, Malaya and India. Lower-grade knitted goods were sold outside the Empire to South China, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. |

China’s Political Conditions Affected Hong Kong IndustriesBecause of its export-oriented character, the development of Hong Kong’s industries was greatly affected by external factors. The Chinese Revolution of 1911, for instance, and the subsequent political unrest that swept the country had far-reaching repercussions. The effects, however, were uneven. Industries that relied on the China market, such as sugar refining, were badly hit, yet the anti-Japanese boycott in the latter part of 1919 stimulated demand for Hong Kong sugar. Some industries benefitted directly from the chaos. The extraordinary demand for military equipment in China boosted the manufacturing of leather and hides. When there was a decline in the export of certain products, such as vinegar, lard and Chinese spirits from China, local manufacturers gained a larger share of the market by stepping up production to make up the short fall. |

Effects of the First World WarThe First World War of 1914-1918 also affected Hong Kong’s industries in a variety of ways. The overall disruption of European shipping, scarcity of tonnage, rise in freight and shrunken demand for consumer goods in Europe had a generally adverse effect. Products that depended primarily on the European market such as rattan furniture, preserved ginger and preserved fruits fell drastically. Shipbuilding and rope making also suffered. Sugar-refining was hit from time to time by the very high price of raw sugar, yet Hong Kong’s refined sugars were able to find new and valuable markets in India and the Persian Gulf. When the export of cement from Germany discontinued, Australia turned to Hong Kong for supply and the industry did well throughout the war years. After the War, many products resumed pre-war levels. The quickest recovery was made by rattan furniture which jumped in export value from $10,000 in 1918 to $380,000 in 1919. |

Industrial Development in the 1930sThe 1930s saw much development in Chinese-owned industries. One significant change that boosted Hong Kong’s industries was the Imperial Preference Policy. Imperial Preference allowed products made in British Colony to enjoy preferential tariff treatment when exported to other parts of the British Empire. In Hong Kong, this stimulated the production of rubber shoes, electric torches and batteries, preserved ginger, cotton knitted goods and silk products. |

The Japanese Invasion of ChinaIronically, the Japanese invasion of China which started in 1937 boosted Hong Kong’s industrial development. Hostilities in China caused many industrialists to relocate their factories to Hong Kong and industries hitherto unknown in the colony came into being. The manufacture of war necessities, such as paint, gas masks, metal helmets, spade and entrenching tools, uniforms and water-bottles, as well as the assembling of field telephones and portable transmitting and receiving sets, grew quickly. |

Industrial EmploymentIn the 19th century, many more workers were engaged in the service sector than in manufacturing. Fewer than 6,800 persons were recorded as being employed in manufacturing in the 1870s. The number climbed to 91,000 in 1921, when the census report shows that many were employed in new industries such as clothing (27.5%), furniture and rattan ware (22.2%) and metal processing (20.6%). By 1931, the number had grown to 100,088, with textiles, clothing, furniture, construction materials and metal refining industries continuing to be the main employers. Notably, many women worked in factories making rubber shoes and boots. |

Labour LegislationThere was no law to regulate industrial employment or factory premises until the 1920s. In 1922 the Industrial Employment of Children Ordinance was enacted, not to limit the age of children working in factories but only to propose the minimum age for different jobs, e.g. children under 15 were not to work in dangerous industries. The Factory (Accidents) Ordinance followed in 1927, which governed the registration and safety operation of factories and workshops. In 1929, the Industrial Employment of Women, Young Persons and Children Amendment Ordinance was passed, barring female workers and young persons from being employed in certain dangerous industries and during specified hours in the evening. The last two ordinances were consolidated into a new one in 1932, which became the basis of legislation governing employment and factory safety in Hong Kong from the 1930s through the Second World War to the 1960s. |

Strikes and Labour MovementsAs industry developed, so did labour movements. While strikes among industrial workers broke out from time to time, none had a bigger impact than the General Strike of 1925, which was followed by a boycott of British shipping and trade in South China. The Strike and Boycott almost paralysed production of every kind in Hong Kong. After this, some unions were labelled as communist and a number of agitators were deported from Hong Kong. In the 1930s, far fewer strikes occurred. |

Hong Kong’s Pre-war Industrial Development – A ReviewBy 1941, just before the Japanese Occupation, when factories were either shut down or confiscated, Hong Kong had built up a flourishing export trade in locally- manufactured goods to China, the neighbouring regions, the British Empire and other distant parts of the world. Not only did it defy the imperial scheme of things by expanding its role beyond a commercial port to that of an industrial centre, it was even competing with British manufactures in a few items in the British home market – the early signs of a phenomenon that was to stun the world in the 1960s and 70s. Since the classic colony was one that exported raw materials and imported manufactured products from Britain, Hong Kong enjoyed a very special status in the British and world history by becoming an industrial colony. |

- {{0+1}}

- {{1+1}}

- {{2+1}}

- {{3+1}}

- {{4+1}}

- {{5+1}}

- {{6+1}}

- {{7+1}}

- {{8+1}}

- {{9+1}}

- {{10+1}}

- {{11+1}}

- {{12+1}}

- {{13+1}}

- {{14+1}}

- {{15+1}}

- {{16+1}}

Shipbuilding and Ship RepairingShip repairing and shipbuilding emerged as major industries as Hong Kong evolved into a commercial and shipping centre. Facilities were simple until John Lamont built a dry dock in Aberdeen in 1857. In 1863, several British firms formed the Hong Kong and Whampoa Dock Company by combining some of the existing docks, including Lamont’s. The company, concentrating its operations in Hunghom from 1880, grew into the largest industrial enterprise in East Asia. The opening of the Taikoo Dockyard and Engineering Company at Quarry Bay in 1907 further enhanced Hong Kong’s shipbuilding capacity. Dockyards operated by Chinese companies included Kwong Hip Lung (established 1877), Ah King’s Slipway (1891) and Tung Hing Loong (around 1897). |

Sugar RefiningSugar refining was another major early industry in Hong Kong. The China Sugar Refinery, operated by Jardine, Matheson & Co., and Taikoo Sugar Refinery, operated by Butterfield & Swire, were the two largest establishments in the 19th century. Hong Kong’s white, refined sugar, was particularly popular in China, Canada, Australia and the United States in the 19th century and it found new markets in India and the Persian Gulf in the early 20th century. |

Chinese ManufacturesApart from the building of small boats, early Chinese-owned industries also included handicrafts such as the making of rattan ware, preserved ginger and fruits. From the early 20th century, Chinese entrepreneurs began investing in a wide range of new industries. The fastest growing one was textile industry, which produced cotton piece goods, knitted vests, socks and silk products. Other important products were furniture, flash lights and battery, and rubber shoes. The processing of metal such as tin and copper was also common. The Chinese Manufacturers’ Union was founded in 1934 to promote Chinese industries and find overseas markets for their goods. This was a good indicator of the prosperity of Chinese manufactures. |

A Traditional Industry – Preserving GingerPreserving ginger, one of Hong Kong’s best known traditional light industries, originated with a Chinese man named Lee. Lee started his career by selling ginger and other pickled foods at a street stall in Guangzhou, and the story goes that one day, an Englishman brought home to England some ginger bought from his stall and it became so popular that he was inundated by orders from England. To meet the demand, Lee founded the Chai Lung ginger factory with two friends, which was later relocated it to Hong Kong in 1846. By 1900, the better known ginger factories in Hong Kong also included Choy Fong's Ginger Factory (翠芳糖薑廠) and Man Loong Ginger Factory (民隆糖薑廠). During the busy seasons, these factories employed over a hundred workers each. Young ginger was imported from Guangzhou, which were then processed and packaged before being exported to markets in Europe, the United States and Australia. In 1937, Hong Kong Exporters Association (香港糖薑經銷商會) was founded to promote new favour, improve packaging and seek new markets. |

1904 – Hong Kong’s First Chinese Textile Factory OpenedHong Kong’s first knitting and weaving factory was founded in 1904 by Chinese investors. Many other Chinese-operated factories followed, the best known being Li Man Hing Kwok, Chow Ngai Hing and Dongya. These factories produced cotton knitted cloth, and in the early days, large factories also turned knitted cloth into cotton vests and socks for the local market. From the 1910s, Hong Kong’s cotton textiles began to compete with Japanese products. In the following decade, Hong Kong enhanced its competitiveness by using more advanced machinery and, as a result, was able to supply not only the local market but also overseas markets such as China and Australia. |

Hong Kong’s Manufactures were Made for ExportHong Kong’s Manufactures were Made for ExportThe majority of Hong Kong’s products were made for export. For many years North China was the largest market for refined sugar followed by India. Preserved ginger fed markets in Britain, Australia, Holland and the United States. Under the Imperial Preference system, knitted piece-goods, electric torches and batteries, and rubber shoes and boots were exported to different places within the British Empire such as India, Malaya, Ceylon, the West Indies and Britain itself, while knitted vests and socks were exported to the West Indies, the Straits Settlements, Malaya and India. Lower-grade knitted goods were sold outside the Empire to South China, the Philippines, and the Dutch East Indies. |

China’s Political Conditions Affected Hong Kong IndustriesBecause of its export-oriented character, the development of Hong Kong’s industries was greatly affected by external factors. The Chinese Revolution of 1911, for instance, and the subsequent political unrest that swept the country had far-reaching repercussions. The effects, however, were uneven. Industries that relied on the China market, such as sugar refining, were badly hit, yet the anti-Japanese boycott in the latter part of 1919 stimulated demand for Hong Kong sugar. Some industries benefitted directly from the chaos. The extraordinary demand for military equipment in China boosted the manufacturing of leather and hides. When there was a decline in the export of certain products, such as vinegar, lard and Chinese spirits from China, local manufacturers gained a larger share of the market by stepping up production to make up the short fall. |

Effects of the First World WarThe First World War of 1914-1918 also affected Hong Kong’s industries in a variety of ways. The overall disruption of European shipping, scarcity of tonnage, rise in freight and shrunken demand for consumer goods in Europe had a generally adverse effect. Products that depended primarily on the European market such as rattan furniture, preserved ginger and preserved fruits fell drastically. Shipbuilding and rope making also suffered. Sugar-refining was hit from time to time by the very high price of raw sugar, yet Hong Kong’s refined sugars were able to find new and valuable markets in India and the Persian Gulf. When the export of cement from Germany discontinued, Australia turned to Hong Kong for supply and the industry did well throughout the war years. After the War, many products resumed pre-war levels. The quickest recovery was made by rattan furniture which jumped in export value from $10,000 in 1918 to $380,000 in 1919. |

Industrial Development in the 1930sThe 1930s saw much development in Chinese-owned industries. One significant change that boosted Hong Kong’s industries was the Imperial Preference Policy. Imperial Preference allowed products made in British Colony to enjoy preferential tariff treatment when exported to other parts of the British Empire. In Hong Kong, this stimulated the production of rubber shoes, electric torches and batteries, preserved ginger, cotton knitted goods and silk products. |

The Japanese Invasion of ChinaIronically, the Japanese invasion of China which started in 1937 boosted Hong Kong’s industrial development. Hostilities in China caused many industrialists to relocate their factories to Hong Kong and industries hitherto unknown in the colony came into being. The manufacture of war necessities, such as paint, gas masks, metal helmets, spade and entrenching tools, uniforms and water-bottles, as well as the assembling of field telephones and portable transmitting and receiving sets, grew quickly. |

Industrial EmploymentIn the 19th century, many more workers were engaged in the service sector than in manufacturing. Fewer than 6,800 persons were recorded as being employed in manufacturing in the 1870s. The number climbed to 91,000 in 1921, when the census report shows that many were employed in new industries such as clothing (27.5%), furniture and rattan ware (22.2%) and metal processing (20.6%). By 1931, the number had grown to 100,088, with textiles, clothing, furniture, construction materials and metal refining industries continuing to be the main employers. Notably, many women worked in factories making rubber shoes and boots. |

Labour LegislationThere was no law to regulate industrial employment or factory premises until the 1920s. In 1922 the Industrial Employment of Children Ordinance was enacted, not to limit the age of children working in factories but only to propose the minimum age for different jobs, e.g. children under 15 were not to work in dangerous industries. The Factory (Accidents) Ordinance followed in 1927, which governed the registration and safety operation of factories and workshops. In 1929, the Industrial Employment of Women, Young Persons and Children Amendment Ordinance was passed, barring female workers and young persons from being employed in certain dangerous industries and during specified hours in the evening. The last two ordinances were consolidated into a new one in 1932, which became the basis of legislation governing employment and factory safety in Hong Kong from the 1930s through the Second World War to the 1960s. |

Strikes and Labour MovementsAs industry developed, so did labour movements. While strikes among industrial workers broke out from time to time, none had a bigger impact than the General Strike of 1925, which was followed by a boycott of British shipping and trade in South China. The Strike and Boycott almost paralysed production of every kind in Hong Kong. After this, some unions were labelled as communist and a number of agitators were deported from Hong Kong. In the 1930s, far fewer strikes occurred. |

Hong Kong’s Pre-war Industrial Development – A ReviewBy 1941, just before the Japanese Occupation, when factories were either shut down or confiscated, Hong Kong had built up a flourishing export trade in locally- manufactured goods to China, the neighbouring regions, the British Empire and other distant parts of the world. Not only did it defy the imperial scheme of things by expanding its role beyond a commercial port to that of an industrial centre, it was even competing with British manufactures in a few items in the British home market – the early signs of a phenomenon that was to stun the world in the 1960s and 70s. Since the classic colony was one that exported raw materials and imported manufactured products from Britain, Hong Kong enjoyed a very special status in the British and world history by becoming an industrial colony. |

- {{0 + 1}}

- {{1 + 1}}

- {{2 + 1}}

- {{3 + 1}}

- {{4 + 1}}

- {{5 + 1}}

- {{6 + 1}}

- {{7 + 1}}

- {{8 + 1}}

- {{9 + 1}}

- {{10 + 1}}

- {{11 + 1}}

- {{12 + 1}}

- {{13 + 1}}

- {{14 + 1}}

- {{15 + 1}}

- {{16 + 1}}