Introduction

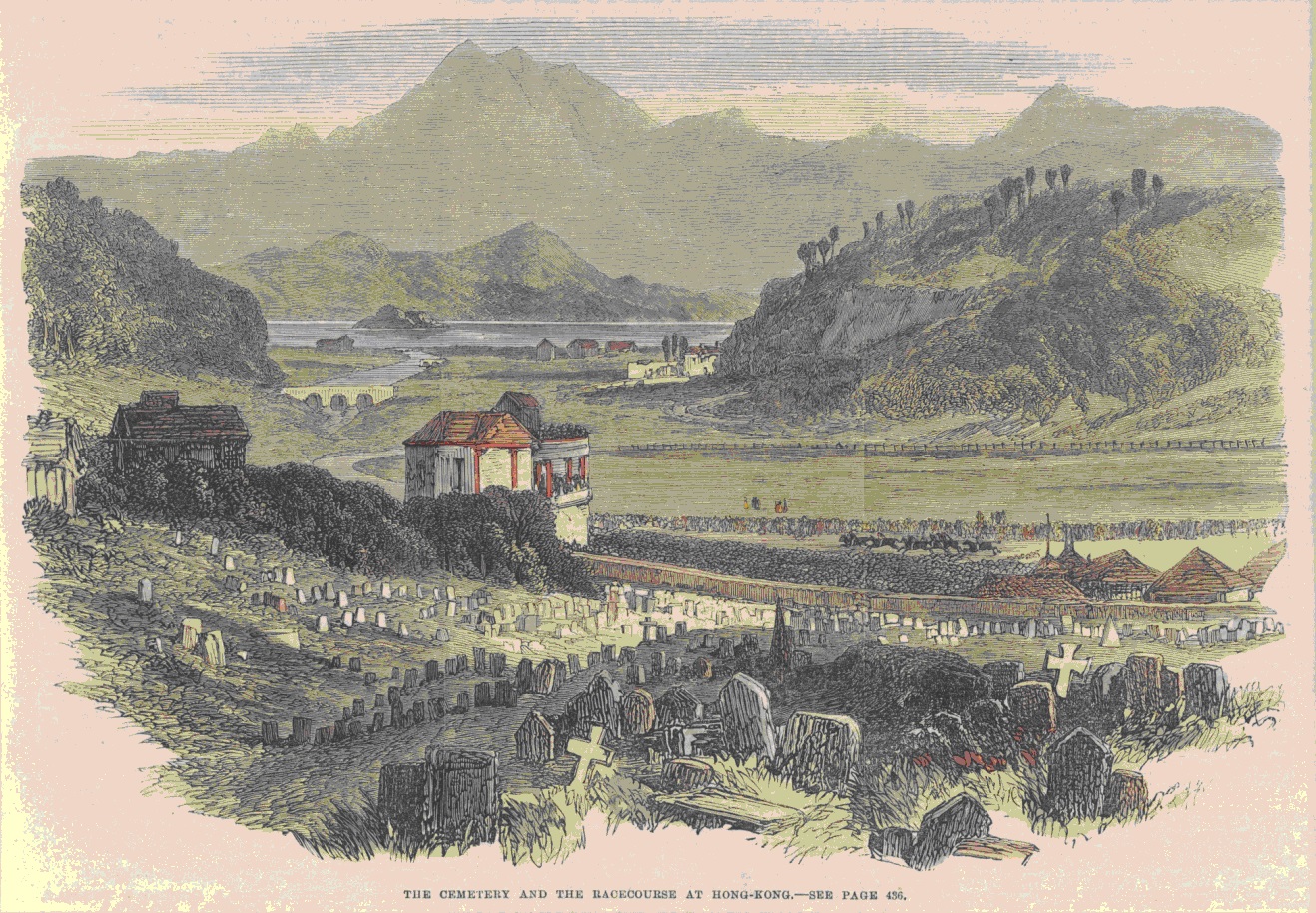

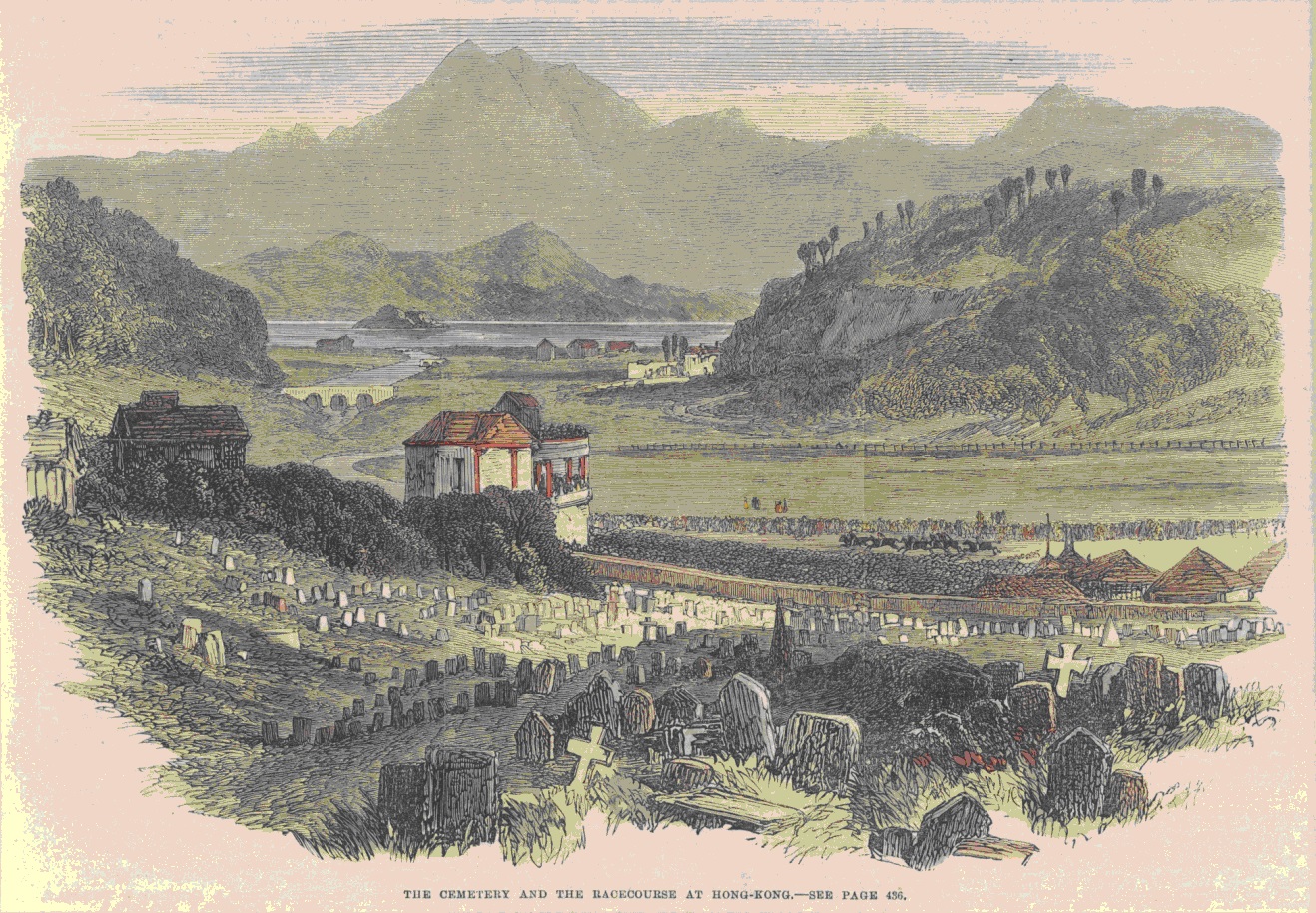

An early print showing the Cemetery and Racecourse from the Illustrated London News, May 1866

The Hong Kong Cemetery was opened in 1845 when Happy Valley was considered too far from town and too mosquito-ridden ever to be needed as building land. The first graves date back even earlier and were moved to Happy Valley in 1889 when Hong Kong’s earliest cemetery in Wanchai was finally closed in 1889. The first monument found belongs to Lieutenant Benjamin Fox who died on 25th May, 1841 of wounds received when the British forces stormed the walls of Canton during the First Opium War. Hong Kong Cemetery was the burial place for all the Protestant and Nonconformist dead for over one hundred years. The Cemetery is a beautiful, inspiring and peaceful place and more importantly it is a significant source of material for students of Hong Kong’s heritage as well as those with a general interest particularly in the fields of history, sociology, genealogy and architecture.

Purpose of Database

Access to the material on site is bedeviled by heat, mosquitoes and the time-consuming problems of finding what one is looking for among the 7000 or so graves scattered over a wide area of hilly ground. For the first time, this database gives the student easy access to this historically important material. Those working in these fields can cross-reference the information from the inscriptions together with added information contained in the notes in order to research many different aspects of Hong Kong’s social and cultural and architectural heritage.

Kinds of Information presented by the database

Valuable information can be extracted on such matters as changes in infant mortality, the age of death of the different classes at different times, and the kinds of employment opportunities offered.

Both the presence and absence of certain groups of people among the Cemetery records can be seen to be significant. For instance the marked absence of governors and their families, merchants and senior civil servants points to their ability to pay for their passage to their home country when they fell ill or retired. Equally the absence in the early decades of poorer whites such as seamen, policemen or lower ranking members of the armed forces demonstrates that they could not afford headstones and were buried in paupers’ graves only marked by numbered stone markers. This means that the graves from the first three decades (1845-1875) represent predominantly the various layers of the middle class.

The database also charts the presence in Hong Kong of minority groups that have helped make Hong Kong into the international city that it is and added to its prosperity and reputation. This includes the 228 Germans, the 107 Americans, the 246 Scotsmen and the 460 Japanese buried there. Hong Kong has also been home to a number of refugees including White Russians fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution. 108 Russian headstones and monuments are to be found in the Cemetery.

The recorded monuments begin with the very beginning of Hong Kong’s history and carry on almost up to the present day. A number belong to the wealthy and famous who set Hong Kong on the path to prosperity and fame such as Sir Catchick Paul Chater, Sir Ho Kai Ho and Sir Robert Ho Tung.. Among the 210 Chinese buried in the Hong Kong Cemetery are some who were known as the founding fathers of Hong Kong and were also well-known among the families close to Dr. Sun Yat Sen. For example, two of the six ‘elders of Hong Kong,’ Kwan Yuen cheung and Wen Qing-xi are buried in this Cemetery. Besides these are two revolutionary figures, Hong Chun-kui (1836-1904) who had the unique distinction of fighting both in the Tai Ping Wars and in an attempted coup against the Imperial forces in Guangzhou led by the revolutionary forces of Dr. Sun Yat-sen in Hong Kong and Yang Quyun, who was an important early leader of the revolutionary forces in Hong Kong and was assassinated there by agents of the Empress in 1901.

The database is an invaluable source of information on architectural trends in the different ages in that every grave in the Cemetery is pictured on it. For instance one can chart how the haphazard lines of simple stones and crosses shown above in the engraving of 1866 were replaced by the beginning of the twentieth century by a planned garden-like cemetery modeled on the Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris where men could stroll at leisure among the trees and flowers Examples are present in the Cemetery of monuments in the nineteenth century gothic style that can be found nowhere else in Hong Kong. The style of lettering used in the inscriptions, the symbols carved on monuments and headstones, the materials used and the differing shapes of the headstones all demonstrate the evolution of different architectural styles over the one hundred and fifty years’ history of the Cemetery.

Introduction

An early print showing the Cemetery and Racecourse from the Illustrated London News, May 1866

The Hong Kong Cemetery was opened in 1845 when Happy Valley was considered too far from town and too mosquito-ridden ever to be needed as building land. The first graves date back even earlier and were moved to Happy Valley in 1889 when Hong Kong’s earliest cemetery in Wanchai was finally closed in 1889. The first monument found belongs to Lieutenant Benjamin Fox who died on 25th May, 1841 of wounds received when the British forces stormed the walls of Canton during the First Opium War. Hong Kong Cemetery was the burial place for all the Protestant and Nonconformist dead for over one hundred years. The Cemetery is a beautiful, inspiring and peaceful place and more importantly it is a significant source of material for students of Hong Kong’s heritage as well as those with a general interest particularly in the fields of history, sociology, genealogy and architecture.

Purpose of Database

Access to the material on site is bedeviled by heat, mosquitoes and the time-consuming problems of finding what one is looking for among the 7000 or so graves scattered over a wide area of hilly ground. For the first time, this database gives the student easy access to this historically important material. Those working in these fields can cross-reference the information from the inscriptions together with added information contained in the notes in order to research many different aspects of Hong Kong’s social and cultural and architectural heritage.

Kinds of Information presented by the database

Valuable information can be extracted on such matters as changes in infant mortality, the age of death of the different classes at different times, and the kinds of employment opportunities offered.

Both the presence and absence of certain groups of people among the Cemetery records can be seen to be significant. For instance the marked absence of governors and their families, merchants and senior civil servants points to their ability to pay for their passage to their home country when they fell ill or retired. Equally the absence in the early decades of poorer whites such as seamen, policemen or lower ranking members of the armed forces demonstrates that they could not afford headstones and were buried in paupers’ graves only marked by numbered stone markers. This means that the graves from the first three decades (1845-1875) represent predominantly the various layers of the middle class.

The database also charts the presence in Hong Kong of minority groups that have helped make Hong Kong into the international city that it is and added to its prosperity and reputation. This includes the 228 Germans, the 107 Americans, the 246 Scotsmen and the 460 Japanese buried there. Hong Kong has also been home to a number of refugees including White Russians fleeing the Bolshevik Revolution. 108 Russian headstones and monuments are to be found in the Cemetery.

The recorded monuments begin with the very beginning of Hong Kong’s history and carry on almost up to the present day. A number belong to the wealthy and famous who set Hong Kong on the path to prosperity and fame such as Sir Catchick Paul Chater, Sir Ho Kai Ho and Sir Robert Ho Tung.. Among the 210 Chinese buried in the Hong Kong Cemetery are some who were known as the founding fathers of Hong Kong and were also well-known among the families close to Dr. Sun Yat Sen. For example, two of the six ‘elders of Hong Kong,’ Kwan Yuen cheung and Wen Qing-xi are buried in this Cemetery. Besides these are two revolutionary figures, Hong Chun-kui (1836-1904) who had the unique distinction of fighting both in the Tai Ping Wars and in an attempted coup against the Imperial forces in Guangzhou led by the revolutionary forces of Dr. Sun Yat-sen in Hong Kong and Yang Quyun, who was an important early leader of the revolutionary forces in Hong Kong and was assassinated there by agents of the Empress in 1901.

The database is an invaluable source of information on architectural trends in the different ages in that every grave in the Cemetery is pictured on it. For instance one can chart how the haphazard lines of simple stones and crosses shown above in the engraving of 1866 were replaced by the beginning of the twentieth century by a planned garden-like cemetery modeled on the Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris where men could stroll at leisure among the trees and flowers Examples are present in the Cemetery of monuments in the nineteenth century gothic style that can be found nowhere else in Hong Kong. The style of lettering used in the inscriptions, the symbols carved on monuments and headstones, the materials used and the differing shapes of the headstones all demonstrate the evolution of different architectural styles over the one hundred and fifty years’ history of the Cemetery.