-

History & Society

- Education in Pre-war Hong Kong

- History of Taikoo Sugar Refinery

- Hong Kong Products Exhibition

- Local Festivals Around the Year

- Post-war Industries

- Pre-war Industry

- The Hong Kong Jockey Club Archives

- Tin Hau Festival

- Memories We Share: Hong Kong in the 1960s and 1970s

- History in Miniature: The 150th Anniversary of Stamp Issuance in Hong Kong

- A Partnership with the People: KAAA and Post-war Agricultural Hong Kong

- The Oral Legacies (I) - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong

- Hong Kong Currency

- Hong Kong, Benevolent City: Tung Wah and the Growth of Chinese Communities

- The Oral Legacies Series II: the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong

- Braving the Storm: Hong Kong under Japanese Occupation

- A Century of Fashion: Hong Kong Cheongsam Story

Geography & EnvironmentArt & Culture- Calendar Posters of Kwan Wai-nung

- Festival of Hong Kong

- Ho Sau: Poetic Photography of Daily Life

- Hong Kong Cemetery

- Sketches by Kong Kai-ming

- The Culture of Bamboo Scaffolding

- The Legend of Silk and Wood: A Hong Kong Qin Story

- Journeys of Leung Ping Kwan

- From Soya Bean Milk To Pu'er Tea

- Applauding Hong Kong Pop Legend: Roman Tam

- 他 FASHION 傳奇 EDDIE LAU 她 IMAGE 百變 劉培基

- A Eulogy of Hong Kong Landscape in Painting: The Art of Huang Bore

- Imprint of the Heart: Artistic Journey of Huang Xinbo

- Porcelain and Painting

- A Voice for the Ages, a Master of his Art – A Tribute to Lam Kar Sing

- Memories of Renowned Lyricist: Richard Lam Chun Keung's Manuscripts

- Seal Carving in Lingnan

- Literary Giant - Jin Yong and Louis Cha

Communication & Media- Hong Kong Historical Postcards

- Shaw Brothers’ Movies

- Transcending Space and Time – Early Cinematic Experience of Hong Kong

- Remembrance of the Avant-Garde: Archival Camera Collection

- Down Memory Lane: Movie Theatres of the Olden Days

- 90 Years of Public Service Broadcasting in Hong Kong

- Multifarious Arrays of Weaponry in Hong Kong Cinema

-

History & SocietyGeography & EnvironmentArt & Culture

-

View Oral History RecordsFeatured StoriesAbout Hong Kong Voices

-

Hong Kong Memory

- Collection

- All Items

- Legacy of Qin

Recently VisitedLegacy of Qin

This article written by Yung Hak-chi, Hammond introduces the succession of qin studies in the Yung Family. Tsar Teh-yun was an important pillar in the legacy of the qin in Hong Kong. This article written by Lau Chor-wah introduces Tsar Teh-yun and the qin community of Hong Kong.

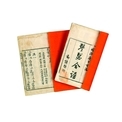

Many qin players, past and present, also know how to make the instrument. This article written by Ng Ying-wai is a brief account of the three generations of qin making in Hong Kong. Qing Rui (1816-1875), a Manchurian native of Heilongjiang who belonged to the Bordered White Banner (Xiangbaiqi), was an accomplished qin and se player. He moved to Guangzhou in 1843 to assume the role of county magistrate in Haikang (present day Leizhou City). According to the records of his grandson, Yung Sum-yin, this picture was taken during the Tongzhi reign (1862-1874). This autobiographic profile was written in 1869 by Qing Rui when he was 53 years old. Here can be found a record of his academic achievements, official positions, place of origin, and the history of his family, etc. The damaged profile was mounted by Jao Tsung-I, a student of Qing Rui’s grandson, Yung Sum-yin in the 1950s.Qinse Hepu was written by Qing Rui during the latter part of his life. It is a collection of qin and se manuscripts comprising two volumes. Eight qin and se ensembles are included in the book, namely Liangxiao Yin (Tune for a Pleasant Evening), Yuqiao Wenda (Dialogue between a Fisherman and a Woodcutter), Pingsha Luoyan (Wild Geese Landing on Sand), Wuye Wu Qiufeng (Parasol Leaves Dancing in the Autumnal Breeze), Cunxiao Yin (Tune for a Spring Dawn), Dongting Qiusi (Autumn Thoughts at Dongting), Shitan Zhang (Stanzas of Siddham), Saishang Hong (Wild Geese on the Frontier). The fingering techniques for the qin and se are displayed side by side on the manuscripts: the right dedicated to those of the se and the left, the qin.

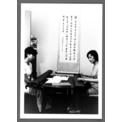

This volume was inscribed for publishing in Guangzhou in the 9th year of the Tongzhi reign (1870) and subsequently published for circulation in the 12th year of the Tongzhi reign (1873). By the 1930s and 1940s, during the time of the Japanese invasion, the Yungs were anxious that the Japanese army would mistake the tablature as coded messages. They therefore destroyed the print blocks of the books, rendering their reprint impossible. Except for the one and only copy of Qinse Hepu handed down in the Yung family, Hong Kong’s qin musicians rarely had the opportunity to read this manuscript before the middle of the last century. Qing Rui's heirloom manuscripts consist of his Qinse Hepu, other qin pieces manuscripts, qin and se ensemble manuscripts, and fingering guides. These recorded the Yung family's one-of-a-kind fingering techniques, as well as their treatment of musical phrases and rhythms. The manuscripts were transcribed from the 1840s to the 1860s. Qing Rui married his second wife, Li Zhixian (1842-1908) during his stay in Southern China. He taught her the art of qin. Li Zhixian played a pivotal role in the succession of qin studies in the Yung family since both the second-generation successor, Yung Bo-ting and the third-generation successor, Yung Sum-yin learnt the art of the instrument from her. This heirloom manuscript contains six qin pieces. They were transcribed by Li Zhixian in the 1880s. The cover of the book was damaged and later restored by Yung Sum-yin in the 1950s, with the qin pieces titles added. Yung Sum-yin (1884-1966) was competent in poetry, calligraphy and xiao (vertical bamboo flute). He was greatly loved by his grandmother, Li Zhixian, and was nurtured, mentored and taught the art of qin by Li Zhixian from an early age. Sum-yin also inherited the manuscripts handed down by Qing Rui. Anxious that the Japanese army would mistake the tablature as encoded messages after the invasion of Guangzhou in 1938, Sum-yin destroyed the original printing blocks of the Qinse Hepu. Yung Sum-yin moved to Hong Kong in 1951, and became one of the earliest qin musicians to settle in the territory.This picture was taken after Yung Sum-yin had settled in the "Manchurian area" of Guangzhou in the 1930s. Yung Sum-yin can be seen in the centre of this photograph playing the qin. The first person on the left is his student, Lo Ka-ping, also a renowned qin musician. Lo also later settled in Hong Kong. These heirloom manuscripts were transcribed in the 1950s. Among them, Yung Sum-yin was particularly fond of Wuxueshanfang Qinpu (Wuxueshanfang Qin Handbook) and Chuncaotang Qinpu (Chuncaotang Qin Handbook). The unconventionally rhythmic and unworldly tuned, Yandu Hengyang (Wild Geese Flying over Hengyang) was his favourite. Yung Sze-chak (1931-2010) was the fourth-generation Yung family successor of qin studies. He could play over 20 qin pieces adeptly, including Pingsha Luoyan (Wild Geese Landing on Sand) in Chuncaotang Qinpu. Yung Sze-chak's heirloom manuscript was transcribed in the 1950s, the calligraphy on the cover was written by Yung Sum-yin on Sze-chak's behalf. "Yinyin" means tranquil and peaceful. The scroll hanging behind Tsar Teh-yun (1905-2007) in this picture is the calligraphy of Yinyinshi Ming (The Commemorative Description of Yinyinshi), written by Tsar Teh-yun. This photo was taken in the 1970s. During a tutorial session, Tsar Teh-yun (right) would place two qins in her room: one for herself and the other for her student. To teach a new piece, she would first demonstrate the complete piece and then explain each section in detail before allowing her student to attempt to play the piece. She would patiently and sincerely demonstrate many passages over and over again if the student was unable to follow. The criticising approach to instruction never existed in her tutelage. This photo was taken in the 1970s.Copyright © 2012 Hong Kong Memory. All rights reserved.

| Set Name |