-

History & Society

- Education in Pre-war Hong Kong

- History of Taikoo Sugar Refinery

- Hong Kong Products Exhibition

- Local Festivals Around the Year

- Post-war Industries

- Pre-war Industry

- The Hong Kong Jockey Club Archives

- Tin Hau Festival

- Memories We Share: Hong Kong in the 1960s and 1970s

- History in Miniature: The 150th Anniversary of Stamp Issuance in Hong Kong

- A Partnership with the People: KAAA and Post-war Agricultural Hong Kong

- The Oral Legacies (I) - Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong

- Hong Kong Currency

- Hong Kong, Benevolent City: Tung Wah and the Growth of Chinese Communities

- The Oral Legacies Series II: the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Hong Kong

- Braving the Storm: Hong Kong under Japanese Occupation

- A Century of Fashion: Hong Kong Cheongsam Story

Geography & EnvironmentArt & Culture- Calendar Posters of Kwan Wai-nung

- Festival of Hong Kong

- Ho Sau: Poetic Photography of Daily Life

- Hong Kong Cemetery

- Sketches by Kong Kai-ming

- The Culture of Bamboo Scaffolding

- The Legend of Silk and Wood: A Hong Kong Qin Story

- Journeys of Leung Ping Kwan

- From Soya Bean Milk To Pu'er Tea

- Applauding Hong Kong Pop Legend: Roman Tam

- 他 FASHION 傳奇 EDDIE LAU 她 IMAGE 百變 劉培基

- A Eulogy of Hong Kong Landscape in Painting: The Art of Huang Bore

- Imprint of the Heart: Artistic Journey of Huang Xinbo

- Porcelain and Painting

- A Voice for the Ages, a Master of his Art – A Tribute to Lam Kar Sing

- Memories of Renowned Lyricist: Richard Lam Chun Keung's Manuscripts

- Seal Carving in Lingnan

- Literary Giant - Jin Yong and Louis Cha

Communication & Media- Hong Kong Historical Postcards

- Shaw Brothers’ Movies

- Transcending Space and Time – Early Cinematic Experience of Hong Kong

- Remembrance of the Avant-Garde: Archival Camera Collection

- Down Memory Lane: Movie Theatres of the Olden Days

- 90 Years of Public Service Broadcasting in Hong Kong

- Multifarious Arrays of Weaponry in Hong Kong Cinema

-

History & SocietyGeography & EnvironmentArt & Culture

-

View Oral History RecordsFeatured StoriesAbout Hong Kong Voices

-

Hong Kong Memory

- Collection

- All Items

- Art of Silk and Wood

Recently VisitedArt of Silk and Wood

As the top boards of qins are made of soft wood, such as Chinese parasol or fir, they are not strong enough to withstand the tension created by the strings. For this reason, the surface of the qin is coated with layers of lacquer base cement and lacquer finish to bear the tension. This article written by Sou Si-tai introduces the technical knowledge pertaining to the lacquering of the qin. The first edition of the Yuguzhai Qinpu (Yuguzhai Qin Handbook), written by Zhu Fengjie of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), was published in 1855. Zhu Fengjie, also known as Tongjun, was a native of Pucheng, Fujian and founder of the Pucheng School of qin. The Yuguzhai Qinpu does not contain any qin tablature. In fact, it is a compilation of the author’s theories on the qin and a discussion covering the aspects of music temperament, qin making, qin practice, and qin playing.

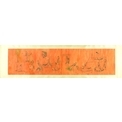

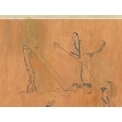

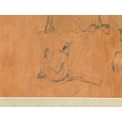

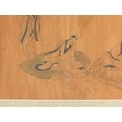

Very detailed information on qin construction can be found in the chapter titled “Qin Construction” in volume 2. Most of the qin making tools described in this volume are still in use today. These include, among others, planes, axes, saws, rasps, drills, round chisels, and square chisels. Gu Kaizhi of the Eastern Jin period was said to be the author of the Zhuoqintu (Illustration of Qin Making). A Song Dynasty silk copy currently resides in the Palace Museum in Beijing. The scroll seen here is a fair copy (2013) made by Li Fei, a member of the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society. The Zhuoqintu depicts different scenes of ancient literati directing craftsmen in the process of qin making. People in the painting are chopping wood, making strings, or testing the qin. Some can be seen observing and giving instructions. Gu Kaizhi of the Eastern Jin period was said to be the author of the Zhuoqintu (Illustration of Qin Making). A Song Dynasty silk copy currently resides in the Palace Museum in Beijing. This extracted piece of scroll - wood chopping is from a fair copy made by Li Fei, a member of the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society. The Zhuoqintu depicts different scenes of ancient literati directing craftsmen in the process of qin making. People in the painting are chopping wood, making strings, or testing the qin. Some can be seen observing and giving instructions. Gu Kaizhi of the Eastern Jin period was said to be the author of the Zhuoqintu (Illustration of Qin Making). A Song Dynasty silk copy currently resides in the Palace Museum in Beijing. This extracted piece of scroll - qin shaping is from a fair copy made by Li Fei, a member of the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society. The Zhuoqintu depicts different scenes of ancient literati directing craftsmen in the process of qin making. People in the painting are chopping wood, making strings, or testing the qin. Some can be seen observing and giving instructions.Gu Kaizhi of the Eastern Jin period was said to be the author of the Zhuoqintu (Illustration of Qin Making). A Song Dynasty silk copy currently resides in the Palace Museum in Beijing. This extracted piece of scroll - sharpening a blade is from a fair copy made by Li Fei, a member of the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society. The Zhuoqintu depicts different scenes of ancient literati directing craftsmen in the process of qin making. People in the painting are chopping wood, making strings, or testing the qin. Some can be seen observing and giving instructions. Gu Kaizhi of the Eastern Jin period was said to be the author of the Zhuoqintu (Illustration of Qin Making). A Song Dynasty silk copy currently resides in the Palace Museum in Beijing. This extracted piece of scroll - hollowing the cavity belly is from a fair copy made by Li Fei, a member of the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society. The Zhuoqintu depicts different scenes of ancient literati directing craftsmen in the process of qin making. People in the painting are chopping wood, making strings, or testing the qin. Some can be seen observing and giving instructions. Gu Kaizhi of the Eastern Jin period was said to be the author of the Zhuoqintu (Illustration of Qin Making). A Song Dynasty silk copy currently resides in the Palace Museum in Beijing. This extracted piece of scroll - string making is from a fair copy made by Li Fei, a member of the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society. The Zhuoqintu depicts different scenes of ancient literati directing craftsmen in the process of qin making. People in the painting are chopping wood, making strings, or testing the qin. Some can be seen observing and giving instructions. Gu Kaizhi of the Eastern Jin period was said to be the author of the Zhuoqintu (Illustration of Qin Making). A Song Dynasty silk copy currently resides in the Palace Museum in Beijing. This extracted piece of scroll - tone testing is from a fair copy made by Li Fei, a member of the Choi Chang Sau Qin Making Society. The Zhuoqintu depicts different scenes of ancient literati directing craftsmen in the process of qin making. People in the painting are chopping wood, making strings, or testing the qin. Some can be seen observing and giving instructions. Selection of materials is of the utmost importance in the process of qin making. The material has to be particularly “light, porous, crisp, and smooth”. Naturally air-dried old Chinese fir, Chinese parasol and Chinese catalpa, that have been stored for years are the best materials for making a qin. On top of possessing good sound qualities, naturally air-dried wood seldom cracks. The top board of the qin is usually made of Chinese fir or Chinese parasol; the bottom board is usually made of Chinese catalpa or other hardwood. The wood for making the qin should have smooth grain lines and even width. There should be no knots or moth damage to the wood. This photo shows the first step of qin making process which was demonstrated by Choi Chang-sau.Chinese fir, a porous material with straight lines, possesses good sound qualities. Selection of materials is of the utmost importance in the process of qin making. The material has to be particularly “light, porous, crisp, and smooth”. Naturally air-dried old Chinese fir, Chinese parasol and Chinese catalpa, that have been stored for years are the best materials for making a qin. On top of possessing good sound qualities, naturally air-dried wood seldom cracks. The top board of the qin is usually made of Chinese fir or Chinese parasol; the bottom board is usually made of Chinese catalpa or other hardwood. The wood for making the qin should have smooth grain lines and even width. There should be no knots or moth damage to the wood. Chinese parasol, tight and detailed lines with interlocking grain; does not crack. Selection of materials is of the utmost importance in the process of qin making. The material has to be particularly “light, porous, crisp, and smooth”. Naturally air-dried old Chinese fir, Chinese parasol and Chinese catalpa, that have been stored for years are the best materials for making a qin. On top of possessing good sound qualities, naturally air-dried wood seldom cracks. The top board of the qin is usually made of Chinese fir or Chinese parasol; the bottom board is usually made of Chinese catalpa or other hardwood. The wood for making the qin should have smooth grain lines and even width. There should be no knots or moth damage to the wood. Chinese catalpa, it is decay-resistant, does not crack, shrink or expand; and has smooth planed surface. Selection of materials is of the utmost importance in the process of qin making. The material has to be particularly “light, porous, crisp, and smooth”. Naturally air-dried old Chinese fir, Chinese parasol and Chinese catalpa, that have been stored for years are the best materials for making a qin. On top of possessing good sound qualities, naturally air-dried wood seldom cracks. The top board of the qin is usually made of Chinese fir or Chinese parasol; the bottom board is usually made of Chinese catalpa or other hardwood. The wood for making the qin should have smooth grain lines and even width. There should be no knots or moth damage to the wood. Qins come in a myraid of styles. In the second step of the qin making process, the design of the qin is drawn onto the wood. The process usually begins with a proposed scheme of measurements for each part, from which paper patterns are drawn. These patterns are next copied onto the wood. To condition and scoop the top and bottom boards into a qin body, the maker must first saw out the qin shape. An axe is next used to chop out the basic shape of the qin, followed by the long plane, which is used to trim and condition the qin top. Using the curve measure as a guide for precision, used for detailed shaping. The qin bottom must be straight along the middle axis. A small curve should be trimmed acorss the sides. This photo shows the second step of qin making process which was demonstrated by Choi Chang-sau. Tools used in the second step of qin making process - chopping:

(1)Paper pattern – drawn to the same scale as the qin,to be copied onto the wood

(2)Pencils – for outlining the qin shape on the top board and bottom board according to the patterns

(3)Hand saw – for sawing out the top board and bottom board as required by the qin style

(4)Axe – for chopping out the basic shape and curve of the qin top

(5)Long plane – for smoothing out the qin top and bottom. The longer the plane is, the flatter and smoother the wood

(6)Short plane – for refining the qin top and bottom

(7)Spokeshave – for creating a rounded edge, e.g. refining the qin forehead

(8)Curve measure – the standard of the curvature of the qin top

(9)Long ruler – the standard of the straightness of the qin top

Copyright © 2012 Hong Kong Memory. All rights reserved.

| Set Name |